Nashville, Tennessee was the largest city on the Western Front during the Civil War. With over 100,000 troops passing through the city from its occupation in 1862 until the end of the war in 1865, there was a real problem with idle troops and prostitutes.

Nashville, Tennessee was the largest city on the Western Front during the Civil War. With over 100,000 troops passing through the city from its occupation in 1862 until the end of the war in 1865, there was a real problem with idle troops and prostitutes.

The state of Tennessee was the last state to join the Confederacy on June 24, 1861. Following a vote by the people, Governor Isham G. Harris proclaimed “All connections by the State of Tennessee with the Federal Union dissolved…Tennessee is a free, independent government.” Nashville became a target of the Union forces due to the city’s importance as a port on the Cumberland River. Its importance as the capital of Tennessee made it a desirable prize. When it became the first Confederate state capital to fall to Union troops, the city was evacuated and Governor Harris issued a call for the legislature to assemble in Memphis.

Text from the March 8, 1862 Harper’s Weekly edition stated:

The commerce of Nashville is very large, being carried on by river and railroads, and by turnpike roads…The average annual shipments are—30,000 bales of cotton, 6000 hogsheads of tobacco, 2,000,000 bushels of wheat, 6,000,000 bushels of Indian corn, and 10,000 casks of bacon. The leading business of the city is in dry goods, hardware, drugs, and groceries. Book publishing is carried on more extensively than in any other Western town, and the publishing house of the Southern Methodist Conference is one of the largest book manufactories in the United States. The value of the taxable property here is $15,000,000.

What exactly does this mean and how did Nashville become so sexy? First, let’s look into a little history of Tennessee. Why was it the last state to leave the Union? It’s complicated. East Tennessee was very pro-Union, comprised of mainly small farmers due to the mountainous terrain. Middle Tennessee was much the same, although the farms were larger. Corn was king unlike cotton of the deep south. That corn made its way throughout the United States, with the British Empire being the biggest consumer of the crop. West Tennessee and Memphis had ties to the cotton of the deep south, however the city of Memphis mainly had allegiance to the banking industry in New York City. Farmers in the state were making a fortune and they didn’t want a war. But, eventually when the Union fired back on Fort Sumter in South Carolina, the people of Tennessee felt that the U.S. government had overstepped its boundaries, and the state begrudgingly tossed in its lot with the Confederacy.

Still, Tennessee remained divided. The town of Shelbyville became known as “Little Boston” because it so vehemently decried the choice to leave the Union. Bedford County, the home of the controversial Confederate General Nathan Bedford Forrest sent as many troops to fight for the Confederacy as it did the Union. When Nashville was occupied by Union forces, there were many Union sympathizers living there, even though it was considered a Confederate capital.

In 1860, before the war began, Nashville had seen an era of economic prosperity. Annual commerce was over $25 million, which was remarkable for a population of slightly less than 20,000 residents, according to the 1860 census. Steamboats had cruised the Cumberland River, and four railroads converged on Nashville. With a major university, a medical school, and numerous academies, scholars from across the South were attracted to Nashville to pursue their education. Publishers called Nashville home and their products enhanced the culture and prestige of the city. There were eight Methodist Churches, three Presbyterian, along with many other denominations, including Baptist, Catholic, Episcopal and Lutheran. This cultural renaissance was complemented by the state capitol building, completed in 1855.

Closer to the river was a shadow district, known as Smokey Row, where an industry catered to the visitors brought into the city on business. This area by the docks thrived on nightlife. The 1860 census names 207 women whose occupation was listed as prostitute; 198 were white and nine were mulatto. Eighty-seven were illiterate; eight could read but not write. Twenty were widows and most were born in Tennessee. They were known as public women. They were called soiled doves, nymphs du pave (girls of the pavement), and frail but fair women. During the Civil War era terms for houses in the district were houses of ill fame, ill repute, bawdy houses, or parlor houses.

U.S. Major General William Rosecrans believed Nashville was an ideal location for his troops. The placement of the city on the rail lines and the Cumberland River made for excellent movement of men and artillery. It appeared to be the perfect spot on the Western Front to gather troops, teach maneuvers, and sharpen tactical abilities for the next round of fighting. Union troops settled into the city, and unexpected trade began to boom. The strong Yankee dollar took over the town. The next four years would see a very different Nashville.

General Rosecrans underestimated the allure of Smokey Row.

Abandoned women began arriving from the industrial cities of the northern states, then from the war ravaged rural areas of the southern states. By 1862, the number of working women in Nashville had increased substantially from the 207 in 1860. Keep in mind that the early Union troops were young volunteers between the ages of 18-22, most of them were away from home for the first time. They were eager to spend their small wages on the soiled doves in the bawdy houses.

By early 1863, Rosecrans and his staff were not only at war against the Confederate Army, they were at war with disease. Syphilis and gonorrhea infections spread through the Union troops. The infections were practically as lethal to soldiers as combat at that time. Almost 9 percent of Union troops would be infected with STDs before the end of the Civil War. The only known way to treat infection was with mercury. Considering that the battle injury rate was 18 percent, the severity of this plague was alarming, with deadly consequences for General Rosecrans’s command.

Religious revivals known as the Second Great Awakening had swept across the country in the mid-1850s. The result of this fervor, particularly in the North, saw women become involved in efforts including temperance, the abolition of slavery, and other reform movements. Due to the spread of STDs first in the military, then into the civilian populations, their cultured, Southern sisters were not far behind them. Demands were made to clean up the city.

Local physicians responded to the dilemma and a Dr. Coleman ran an advertisement in which he announced that he had opened a Dispensary for Private Diseases. Another physician, Dr. A. Richard Jones, opened a medical office offering the same service on Dederick Street.

Meanwhile, Capt. Ephraim Wilson described the first major attempt to control wartime prostitution: “During the winter of 1862-63, the Army had a social enemy to contend with which seriously threatened its very existence…the women of the town.”

Union officials decided on what they believed to be the easiest solution. Since they couldn’t stop soldiers from visiting local prostitutes, something had to be done to move the girls out of Nashville. The movement to legalize prostitution in Nashville began in June 1863, when Brigadier General R. S. Granger noted that officers and medical staff petitioned him to “save the army from venereal disease, a fate worse . . . than to perish on the battlefield.”

Capt. Wilson continued to document the situation, “Fifteen hundred of them at a single time were gathered up and placed aboard a train and were compelled to leave and conducted under guard to Louisville.” Louisville at first objected to receiving such a formidable array of unwelcome guests, but finally consented to do so, and Nashville was afterward all the happier and better off for their conspicuous absence.” But, the women had not agreed to this relocation plan and were soon back in Nashville.

At the same time, a frailer group of women were placed on board a steamship name the Idahoe. (Yes, you read the name correctly. Truth is always stranger than fiction.) Louisville refused to take them since they were sick, and due to concerns that there may be Confederate spies among them, and the steamer headed for Cincinnati. That city refused them as well. It should be noted that at both ports men swam the river and attempted to climb on board when they heard news that a steamship filled with women of easy virtue was approaching. Union troops shot at the men to keep them from climbing on board. The women, knowing that they had lost income at both ports, destroyed the interior of the steamer. The owner never recouped his losses and the ladies were returned to Nashville.

The problem became increasingly worse. The Union Army had overlooked a basic, strategic factor which no army should ignore – that of supply and demand.

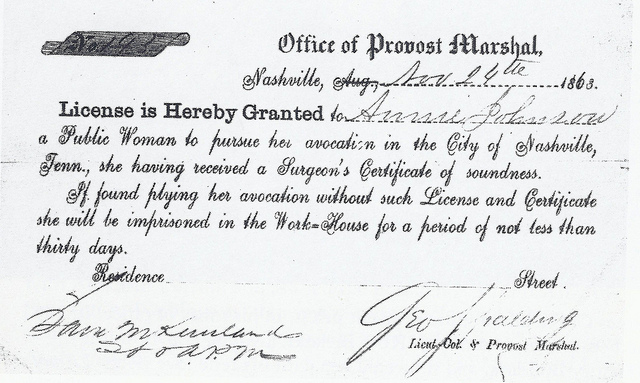

Finally, in an attempt to regulate the spread of disease, a referendum was passed where prostitutes had to be examined, declared disease free, treated and given a license to practice their trade. The Union Army in Nashville established the United States’s first system of legalized prostitution.

The plan was simple. Each lady would register and receive a license for $5, which allowed her to freely practice her trade. An Army doctor examined the girls each week at an additional 50 cent fee, to ensure they remained disease free. Those who had caught a disease were sent to a hospital established specifically for them. Anyone found ‘working’ without a license, or those who didn’t appear for a weekly examination were arrested and sentenced to 30 days in jail.

Once suspicious of the military laws because of the treatment they had received, Nashville’s soiled doves took to the new system with as much enthusiasm as those who established it. One doctor penned that they no longer had to turn to “quacks and charlatans” for ineffective treatments, and eagerly showed potential customers their licenses to prove that they were disease-free.

The war ended, the soldiers moved on, and the women went their way, too. Nashville became the Music City in the 20th Century and is a global publishing hub. As for the ladies, they probably did a great deal to boost morale, and the coffers of the city, especially as the war became longer and deadlier than anyone ever imagined. These women offered their talents, and we have to admire their courage, feel their suffering, and acknowledge their ability to survive during this tragic era in our nation’s history.

Deb Hunter writes fiction as Hunter S. Jones, publishing as an indie author, as well as through MadeGlobal Publishing. She is a member of the prestigious Society of Authors founded by Lord Tennyson, Society of Civil War Historians (US), Dangerous Women Project Global Writers Initiative (University of Edinburgh), Romance Writers of America (PAN member), Historical Writers’ Association, Historical Novel Society, English Historical Fiction Authors, Atlanta Writers Club, Atlanta Writers Conference, and Rivendell Writers Colony which is associated with The University of the South. Originally from Chattanooga, Tennessee, she now lives in Atlanta, Georgia with her Scottish born husband.

Website | Twitter | Instagram | Facebook | Amazon

Sources

Sexual Misbehavior in the Civil War: A Compendium of 1,036 True Stories. Thomas P. Lowry, Xlibris Press, 2006. (He notes the terms whore, whorehouse, and bordello were infrequently used terms during the Civil War era.)

The Story the Soldiers Wouldn’t Tell: Sex in the Civil War. Thomas P. Lowry. Stackpole Press, 1994.

Charles Smart, ed., The Medical and Surgical History of the War of the Rebellion, Part III, vol. II, Medical Volume. District of Columbia, 1888.

U.S. Census Bureau (1860). Tennessee State Government Archives, History. Retrieved from http://Tennessee Electronic Library (TEL).

“A Strange Cargo,” Cleveland Morning Leader, July 21, 1863.

“Harper’s Weekly,” March 8, 1862.

“The Curious Case of Nashville’s Frail Sisterhood.” Angela Serratore, Smithsonian Magazine, 2013.

“City’s Civil War ‘Secret’ Revealed,” George Zepp, The Tennessean, 2003.

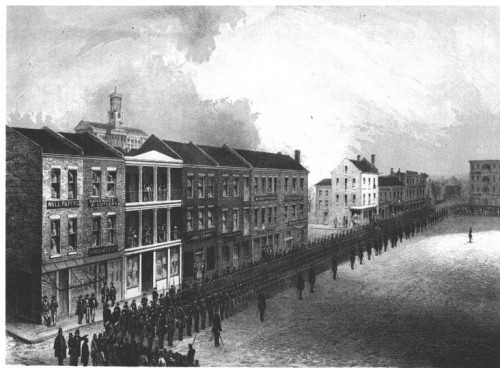

Photograph of the Nashville Wharf, taken by Calvert Brothers, shortly after the Civil War. From the Tennessee State Library and Archives.

Nashville under Union occupation, c. 1863. Library of Congress.

Nashville prostitution license, 1863. National Archives.

All photographs are public domain or owned by the author.

Wow, fantastic illustrations. Thanks for sharing ❤

LikeLike

Thank you, Christoph! I appreciate your insights. ❤

LikeLike

Great article, Deb! I’ve always been fascinated with the civil war . You’ve given me some great thinking material! Thanks!

LikeLike

Thank you so much for stopping by today! It’s always great to know your work is appreciated. Cheers!

LikeLike

Thank you so much for having me as a guest today, Jessica! This was fantastic.

LikeLike

Thank you for stopping by! Love the post! 🙂

LikeLiked by 1 person

Your love for history is rubbing off on me. It is a fascinating time! Thanks for sharing.

LikeLike

We have no idea what people went through until we take a peek. We think it’s all war, battles, women writing love notes & working as nurses…uh, not really. Thanks for the props!

LikeLike

Reblogged this on Exile on Peachtree Street and commented:

Thanks to Dirty, Sexy History for spotlighting my Civil War story today!

LikeLike

Thanks for sharing.

LikeLike

Thank you!

LikeLike

This was fascinating, Deb! There is always so much “hidden” history (especially social history) that is as, if not more, interesting than what is usually shared and studied.

LikeLike

There really is. You can imagine how shocked modern Nashville was to learn about this a few years ago. Thanks so much for stopping by!

LikeLiked by 1 person

That’s such an interesting story to know. I don’t know much about US history, so thank you for sharing it ❤

LikeLike

Thank you Stef. We’ve packed a lot of stuff into a short amount of time. Have a fun weekend!

LikeLike

Fascinating! I loved this. Had to share…

LikeLike

Thank you for that!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Interesting tidbits about the Civil War. Sharing on Twitter.

LikeLike

Thanks so much!

LikeLike

Very interesting. I don’t know if it was my Georgia education or not, but I mostly only learned about Georgia and South Carolina and the major battles of Virginia. I don’t know if Tennessee was ever mentioned.

LikeLike

Thank you for stopping by! Yep, each state has it’s own curriculum, so who knows? We weren’t taught this in TN, that’s for sure. 🙂

LikeLike

I have always loved Nashville. Great article.

LikeLike

Many thanks, Christian! Glad you enjoyed it. Cheers!

LikeLiked by 1 person

HeHe…transporting working girls on a steamship called “Idahoe”…if only it were intentional! Squeezing a story of adult commerce out of the Civil War era records, brilliant…and why am I not surprised? :-p Great job Ms Jones ❤

LikeLike

These stories are fantastic – fund myself telling someone keen on Civil War history the history of the ‘Idahoe’. My father has a naval background and it was fascinating from that perspective too. No supplies or money? Those women would have been fighting like cats and dogs.

LikeLike