“I should much wish, like the Indian Vishna, to float along an infinite ocean cradled in the flower of the Lotus, and wake once in a million years for a few minutes – just to know that I was going to sleep a million years more.” – Samuel Taylor Coleridge

While the medicinal properties of opium have been known since prehistoric times, it was 16th century Swiss alchemist Paracelsus who first developed laudanum. He discovered that when mixed with alcohol as opposed to water, opium’s pain-killing properties were heightened. He mixed it with crushed pearls, musk, saffron, and ambergris* and called it laudanum, from the Latin word laudare: to praise.

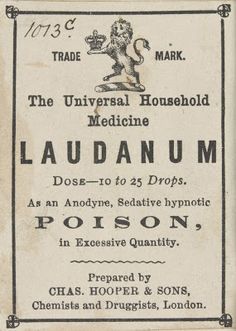

Now thought of as primarily a Victorian drug, laudanum first reached England in the 1660s when physician Thomas Sydenham developed his own recipe. While Sydenham left out the ambergris, the fundamentals remained the same: alcohol and opium was a potent cure-all and in his Medical Observations Concerning the History and Cure of Acute Diseases (1676), he gave it the praise Paracelsus had predicted a century before. Laudanum took off during the eighteenth century and by the nineteenth, it could be found in almost every home in Britain.

Although the recipe was flexible, it remained at heart an uncomplicated but potent combination of alcohol and opium. It was an over the counter drug cheap enough to be used across the social spectrum and simple enough to be brewed at home. Laudanum was used for an endless list of ailments including but not limited to teething, insomnia, anxiety, nerves, hysteria, menstrual cramps, pregnancy pains, mood swings, depression, stomach upset, diarrhea, consumption, cough, heart disease, and cholera.

It was certainly an effective cough suppressant; related opioids such as morphine and codeine are still prescribed for cough today. It was a potent painkiller, induced deep sleep and vivid dreams, produced feelings of euphoria, and was addictive as it was cheap. Not to be limited to medicinal purposes, laudanum was taken recreationally or mixed with other alcohol such as absinthe to stimulate creativity among artists. Some notable fans of the substance include Dickens, Bram Stoker, Samuel Taylor Coleridge, George Elliott, Dante Gabriel Rossetti, and Rossetti’s wife, model Elizabeth Siddal, who tragically died of a laudanum overdose.

Women tended to be medicated more than men, and many opium-derived medications were known euphemistically as “Woman’s Friend.” Likewise, Godfrey’s Cordial, a mixture of water, treacle, and opium specifically for infants was knows as “Mother’s Friend.”

Charles Kingsley describes opium addiction in Alton Locke (1850) as ‘elevation’, a particular problem of women:

“Oh! ho! ho! — yow goo into druggist’s shop o’ market-day, into Cambridge, and you’ll see the little boxes, doozens and doozens, a’ ready on the counter; and never a ven-man’s wife goo by, but what calls in for her pennord o’ elevation, to last her out the week. Oh! ho! ho! Well, it keeps women-folk quiet, it do; and it’s mortal good agin ago pains.” “But what is it?” “Opium, bor’ alive, opium!”

There were several different laudanum varieties available and they could be made at home. It was dreadfully bitter, so sweeteners like honey and spice were added to improve the flavor. Sydenham’s recipe from 1660 was still in use by the 1890s when it was published in William Dick’s Encyclopedia of Practical Receipts and Processes:

“Sydenham’s Laudanum: This is prepared as follows: opium, 2 ounces; saffron, 1 ounce; bruised cinnamon and bruised cloves, each 1 drachm; sherry wine, 1 pint. Mix and macerate for 15 days and filter. Twenty drops are equal to one grain of opium.”

Dick’s Encyclopedia contains dozens of recipes for homemade laudanum, and even more for other remedies containing opium. As relatively appealing as cinnamon and cloves sound, by the 19th century, laudanum could also be mixed with mercury, ether, chloroform, hashish, or belladonna; if it didn’t kill you, it would make you see some very interesting things.

Whether or not the malady justified the use of such a powerful drug, laudanum and other opium derivatives were used frequently and without a great deal of hesitation. It was a good cough suppressant, kept children quiet, and induced restful sleep. Rhapsodic descriptions of its effects make it sound like magic.

In The Picture of Dorian Gray, Oscar Wilde conveys the horrors and pleasures of an East End opium den in a single paragraph (it isn’t exactly laudanum, but it’s the same active ingredient):

“As Dorian hurried up its three rickety steps, the heavy odour of opium met him. He heaved a deep breath, and his nostrils quivered with pleasure. When he entered, a young man with smooth yellow hair, who was bending over a lamp lighting a long thin pipe, looked up at him and nodded in a hesitating manner. […] Dorian winced and looked round at the grotesque things that lay in such fantastic postures on the ragged mattresses. The twisted limbs, the gaping mouths, the staring lustreless eyes, fascinated him. He knew in what strange heavens they were suffering, and what dull hells were teaching them the secret of some new joy.”

Strange heavens aside, laudanum was not a friendly substance. In 1889, The Journal of Mental Sciences published what was purported to be an anonymous letter by the wonderful title of Confessions of a Young Lady Laudanum-Drinker which describes at length her experience of addiction:

“It got me into such a state of indifference that I no longer took the least interest in anything, and did nothing all day but loll on the sofa reading novels, falling asleep every now and then, and drinking tea. Occasionally I would take a walk or drive, but not often. Even my music I no longer took much interest in, and would play only when the mood seized me, but felt it too much of a bother to practice. I would get up about ten in the morning, and make a pretence of sewing; a pretty pretence, it took me four months to knit a stocking!

“Worse than all, I got so deceitful, that no one could tell when I was speaking the truth. It was only this last year it was discovered; those living in the house with you are not so apt to notice things, and it was my married sisters who first began to wonder what had come over me. By that time it was a matter of supreme indifference to me what they thought, and even when it was found out, I had become so callous that I didn’t feel the least shame. (…) My memory was getting dreadful; often, in talking to people I knew intimately, I would forget their names and make other absurd mistakes of a similar kind. As my elder sister was away from home, I took a turn at being housekeeper. Mother thinks every girl should know how to manage a house, and she lets each of us do it in our own way, without interfering. Her patience was sorely tried with my way of doing it, as you may imagine; I was constantly losing the keys, or forgetting where I had left them. I forgot to put sugar in puddings, left things to burn, and a hundred other things of the same kind.”

While this anonymous writer did recover, laudanum addiction was difficult to beat. People became tolerant to it quickly, and recovery was more likely to be achieved by tapering doses. Although laudanum was a common cough suppressant, it could work too well by causing shortness of breath and respiratory depression, or keeping the user from breathing at all. It can also inhibit digestion, cause constipation, depression, and itching. It was so potent that it was easy to overdose accidentally as an adult, and many infants and children died from it as well. Tragically, it was also a common method of suicide.

We might not understand the appeal of such a debilitating and ultimately lethal substance, but for most people in the nineteenth century, laudanum must have felt like a godsend. Disease, poverty, and hunger were widespread, and those lucky enough to be employed suffered through long hours in terrible conditions to earn their pittance. Even for the wealthy and well-to-do, Britain was cold, wet, and overrun with discomforts that may necessitate its use. Menstrual cramps, insomnia, anxiety, nerves, cough, stomach upset, cholera, tuberculosis — if one drug could treat them all and that drug happened to be miraculously affordable and so common there was little to no stigma attached to it, there was no reason not to rely on it from time to time.

We might not understand the appeal of such a debilitating and ultimately lethal substance, but for most people in the nineteenth century, laudanum must have felt like a godsend. Disease, poverty, and hunger were widespread, and those lucky enough to be employed suffered through long hours in terrible conditions to earn their pittance. Even for the wealthy and well-to-do, Britain was cold, wet, and overrun with discomforts that may necessitate its use. Menstrual cramps, insomnia, anxiety, nerves, cough, stomach upset, cholera, tuberculosis — if one drug could treat them all and that drug happened to be miraculously affordable and so common there was little to no stigma attached to it, there was no reason not to rely on it from time to time.

Laudanum is still in production today, but it is no longer available over the counter. Now referred to almost exclusively as Tincture of Opium, it is listed as a Schedule II substance due to its highly addictive nature and is used for stomach ailments, pain, and to treat infants born to mothers with opioid addiction.

Jessica Cale

Sources

Anonymous. Confessions of a Young Lady Laudanum-Drinker. The Journal of Mental Sciences January 1889

Berridge, Victoria. “Victorian Opium Eating: Responses to Opiate Use in Nineteenth-Century England,” Victorian Studies, 21(4) 1978.

Dick, William B. Encyclopedia of Practical Receipts and Processes. New York: Dick & Fitzgerald, Publishers, 1890.

Diniejko, Andrzej. Victorian Drug Use. The Victorian Web. http://www.victorianweb.org/victorian/science/addiction/addiction2.html

Kingsley, Charles. Alton Locke (1850).

O’Reilly, Edward. Laudanum: A Dose of the Nineteenth Century.

Sydenham, Thomas. Medical Observations Concerning the History and Cure of Acute Diseases (1676)

Wilde, Oscar. The Picture of Dorian Gray (1890).

*presumably crushed diamonds would have been too extravagant

Great post. Thanks, Jessica.

Tweeted 🙂

Kimberly

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks, Kimberly! Much appreciated!

LikeLike

Thanks, Jessica. I get so tired of people claiming problems like drug addiction never happened in the good old days. If they only knew!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Right! I understand nostalgia, but people don’t really change. That doesn’t detract from the appeal of history, though — the more we can relate to the past, the more interesting it is (in my opinion). Thank you for stopping by! 🙂

LikeLike

Really enjoyed this article 🙂

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks, Laura! It was fun to write! 🙂

LikeLike

Thanks – what an interesting post! Using in America seemed more “workaday,” with not as much literature and art generated – I guess we waited til the psychedelic 60s to make our contribution to drug-inspired art. The dosages people attained are unbelievable.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks very much, Jean! It’s hard to imagine how people were able to function on such high dosages, but from what I understand, they became tolerant to it quite quickly and then it was difficult to function without it. It’s surprising how common it was, given the side effects. I suppose we should be grateful for all of the art that came out of it, and that our cough medicine is safer now. 😉 Thanks for stopping by!

LikeLike

[…] A history of Victorians’ favorite drug: laudanum. […]

LikeLike

[…] Dirty Sexy History: Suffering in Some Strange Heaven: An Introduction to Laudanum […]

LikeLike