Today we have CSI: Every City in America and then Some. Patricia Cornwell makes a killing with her Scarpetta series. People binge watch Making of a Murderer. But in Victorian England, citizens had no such luxurious entertainments. When murder didn’t come to them, they went to the murder.

The murder tourism trade was rampant during the Victorian era in England as the time saw a powerful focus on death and dying. Victorians took on many rituals surrounding death, developing traditions during periods of mourning, and maintaining keepsake notions like clipping a lock of hair from a dead person and keeping it in a locket, and even death photos in which the dead were photographed. This delight with death sparked a surge in entertainments focused on murder.

Murder tours were all the rage. The Radlett murder in 1823 sparked a wealth of murder entertainment. The Radlett murder involved three men mired in the vices of gambling and boxing who killed a fourth man, William Weare. The three murderers were led by John Thurtell, a sports promoter. He believed Weare had cheated him out of money and murdered him on October 24, 1823. Tourists would visit the location of the murder, a cottage in Radlett, Hertfordshire, England to survey the scene of the crime. Even Sir Walter Scott would visit the cottage a few years after the crime.

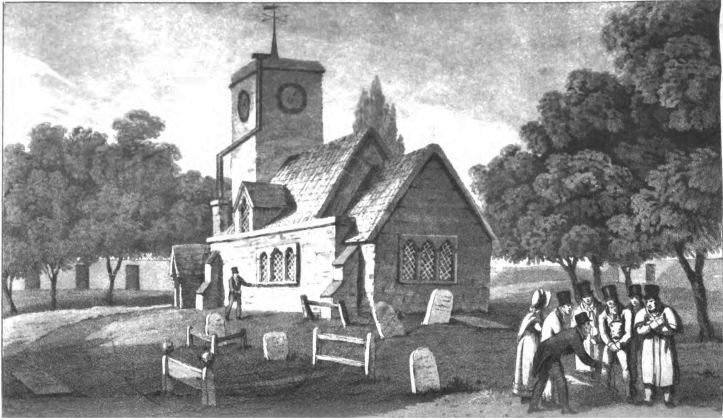

Tourists flocking to murder scenes was so common, a trade built up around it. Sightseeing tours to murder locations became quite common. In relation to the Radlett murder, the tour would take visitors not only to the cottage where the murder took place but to the local churchyard and the pond where the murderers hid. Finally the tour would stop at the Artichoke Inn, the place where the corpse was carried during the execution of the murder, and the proprietor of the inn, a Mr. Field, would be required to answer questions of the visitors.

So popular were these tours, that tradesmen began to capitalize on them by creating souvenirs for tour-goers. In the case of the Radlett murder, at the end of the tour you could acquire a bit of the sack that was used to carry the corpse of William Weare or a book and a map of the murdered body’s journey. Staffrodshire pottery was even developed around the murder. But tourists took it even further.

When news of a murder got out, murder-hungry tourists would race to the location in the hopes of a public auction. Fanatics would buy up any materials that were auctioned off in the hopes of getting something from the murder scene. When that wasn’t enough, they would flock to the executions to see the murderers hanged. In the case of John Thurtell, an estimated 40,000 people attended. But it wasn’t just the crime scenes and mementos that pulled in the tourists. Murder spawned entertainment of a much more creative nature as well.

Murder plays and poetry abounded from sensational murders. Poetry accompanied action illustrations in broadsheets published during murder trials at the height of public frenzy. In the case of the Radlett murder, Thurtell once again was the focus with –

From bad to worse he did proceed,

‘mid scenes of guilt and vice,

Until he learn’d the cursed art,

To play with cards and dice.

Spectators would buy up these broadsheets, especially if they couldn’t afford newspapers. These publications would feed their yearning for more sensation as the trial went on. But even more so did plays move to stoke the public’s interest.

The Gamblers, or, The Murderers at the Desolate Cottage opened at the Surrey on November 17, 1823, not one month after the murder. The Gamblers would reappear on stage immediately following Thurtell’s execution. So hungry for murder plays was the public that it was not uncommon for plays based on real-life murders to play over and over again to packed houses.

While it may seem uncouth or perhaps disrespectful to the dead for people to carry on so, I bring you back to the present where the recent adaptation for television of the O.J. Simpson trial won an Emmy for outstanding limited series. Perhaps we’re not all that different from Victorians. Perhaps it’s just that advancements in technology has changed how people revel in the forbidden of murder. Getting safely close to the danger of murder through entertainments like shows and books. Perhaps now murder simply comes to us.

Jessie Clever

Sources:

Flanders, Judith. The Invention of Murder: How the Victorians Revelled in Death and Detection and Created Modern Crime. New York: St. Martin’s Press, 2011, pp. 20-41.

About Jessie Clever

In the second grade, Jessie began a story about a duck and a lost ring. Two harrowing pages of wide ruled notebook paper later, the ring was found. And Jessie has been writing ever since.

In the second grade, Jessie began a story about a duck and a lost ring. Two harrowing pages of wide ruled notebook paper later, the ring was found. And Jessie has been writing ever since.

Taking her history degree dangerously, Jessie tells the stories of courageous heroines, the men who dared to love them, and the world that tried to defeat them.

Jessie makes her home in the great state of New Hampshire where she lives with her husband and two very opinionated Basset Hounds.

Her most recent release is To Be a Debutante: A Spy Series Short Story. Find out more at jessieclever.com.

An very intriguing look into the history and development of tourism. heh. Not all victorian tours were about archaeology (egyptology)!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks for reading! 🙂

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you so much for having me today!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you so much for stopping by! Looking forward to your next post! 🙂

LikeLike

Very informative and entertaining post. Thank you! .

LikeLiked by 1 person

[…] Source: The Tourist Trade Was Murder in Victorian England […]

LikeLike

Reblogged this on spiritofnlm.

LikeLiked by 1 person