I write mysteries set in Elizabethan England featuring Francis Bacon as my primary sleuth. No one knows for sure — no love letter from Bacon to another person has survived. He isn’t likely to have written such things, in my opinion, because he was a courtier practically from birth and knew better than to write down anything that could be used against you later. But most historians believe he was a man who preferred men, sexually. The evidence is slender; such as there is I discussed on my blog.

I write mysteries set in Elizabethan England featuring Francis Bacon as my primary sleuth. No one knows for sure — no love letter from Bacon to another person has survived. He isn’t likely to have written such things, in my opinion, because he was a courtier practically from birth and knew better than to write down anything that could be used against you later. But most historians believe he was a man who preferred men, sexually. The evidence is slender; such as there is I discussed on my blog.

Based on that slender evidence, my version of Francis Bacon is decidedly gay, to use the modern term. So I need to understand what that would have meant in his time. Toward that end, there is no better resource than Alan Bray’s excellent Homosexuality in Renaissance England (1996, Columbia University Press.)

This book is not only a clear-eyed, detailed resource on the stated topic, but also a fine example of historical writing, on both technical and stylistic grounds. Read this together with Alan Haynes’ Sex in Elizabethan England and you’ll learn the difference between history and literature-based speculation. Bray’s thesis is that a study of homosexuality ought properly to belong in a general study of interfamilial relations.

He begins quite correctly with a discussion of his sources. He notes that most of our ideas about homosexuality in early modern England derive from Havelock Ellis’ provocative 1897 Sexual Inversion. Ellis was trying to create a new culture; he was not writing a history book. It’s not much help for those of us who try to cleave to the actual as much as possible.

The slippery slope

Bray notes on page 9, “There was an immense disparity in this society [early modern England] between what people said — and apparently believed — about homosexuality and what in truth they did.” Thank goodness! What people said was pretty horrible. Diatribes and sermons of the time displayed a persistent association between unnatural acts, homosexual sex and bestiality. Boys + goats = demonic debauchery.

Bray notes on page 9, “There was an immense disparity in this society [early modern England] between what people said — and apparently believed — about homosexuality and what in truth they did.” Thank goodness! What people said was pretty horrible. Diatribes and sermons of the time displayed a persistent association between unnatural acts, homosexual sex and bestiality. Boys + goats = demonic debauchery.

Strictly speaking, nobody ranted about homosexuality, because the term wasn’t coined until the late nineteenth century. The earlier term was ‘sodomite;’ gritty and biblical, meant to be shocking. Like ‘atheist,’ the word had more to do with outlawry and social nonconformity, — behaving in a manner contrary to the laws of man, God, and nature — than with sex. Nobody you liked and respected was ever a sodomite. It was a word you hurled at someone you were trying to injure.

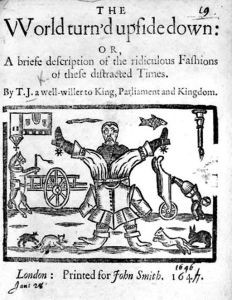

Turned upside down

There was plenty of ranting, some of it truly vile. The odious Sir Edward Coke thought buggery was treason against the King of Heaven. (Coke was one of Bacon’s lifelong rivals; for this and other reasons I despise him.) Bray reviews the rantings and discusses the reasons people were so fearful about overturning God’s laws. If you go too far, you risking turning the whole world upside down. Chaos would result. We’d all go mad!

There was plenty of ranting, some of it truly vile. The odious Sir Edward Coke thought buggery was treason against the King of Heaven. (Coke was one of Bacon’s lifelong rivals; for this and other reasons I despise him.) Bray reviews the rantings and discusses the reasons people were so fearful about overturning God’s laws. If you go too far, you risking turning the whole world upside down. Chaos would result. We’d all go mad!

Bray also gives us a look at the caricatures drawn in early modern literature: “…the sodomite is a young man-about-town, with his mistress on one arm and his ‘catamite’ on the other; he is indolent, extravagant and debauched.” The Earl of Oxford fit this portrait perfectly. Note that this man-about-town was omnisexual — depraved in all directions.

Lots of storm, little fury

Bray examines court records for hints about interpersonal relations. Buggery cases were heard in the Quarter Assizes, judged by county Justices of the Peace. While the crime was a felony, cases were rare. In the 66-year period 1559-1625, in all of Kent, Sussex, Hertfordshire, and Essex, there were only 4 indictments for sodomy. These cases involved violence and were thus breaches of the peace. Nobody was sneaking around spying out naughty buggers and hauling them into court; not even into church courts.

Bray situates garden variety homosexuality inside the home, observing that homes in early modern times were also workplaces. The workshop was on the ground floor of the house or in the yard. A typical path for a young person, male or female, was to leave the natal home in the early teens and go off to work in someone else’s house. Boys might be apprenticed to a craftsman; girls would find work as servants. They would work until they were able to support themselves, through savings and advancement in their craft.

In early modern England, as now, couples were expected to establish independent households. They married later as a result; men well into their twenties or even thirties, women around mid-twenties. Note that this is also an effective means of managing the birth rate; pretty much the only means they had other than abstinence.

Servants and apprentices lived with the family, though they might sleep on cots in the attic or in a cockloft over the barn, segregated by sex. Thus there were many opportunities for opportunistic sexual relations; desirable as a way of relieving sexual pressures without producing unwanted pregnancies.

Neither ask thou, nor tell

Bray concludes that, “In general homosexual behaviour went largely unrecognised or ignored, both by those immediately involved and by the communities in which they lived.” Vehement hostility in public was matched by willing blind complicity in private.

Bray notes that Francis Bacon was known to have sexual relations with his servants, which no one would have minded if he hadn’t been so outrageously generous with gifts, for which he probably borrowed the money. He quotes Aubrey’s Life of Francis Bacon: “He was a παιδεραστής. [paiderastes~pederast] His Ganymedes and favourites took bribes; but his lordship always gave judgement secundum aequum et bonum [according to what is just and good.] His decrees in Chancery stand firm, i.e. there are fewer of his decrees reversed than of any other Chancellor.”

Thus we see that Bacon may have been queer, but he was also always fair.

Anna Castle

References

Bray, Alan. 1996. Homosexuality in Renaissance England. Columbia University Press.

Award-winning author Anna Castle writes two historical mystery series: the Francis Bacon mysteries and the Professor & Mrs. Moriarty mysteries. She has earned a series of degrees — BA in the Classics, MS in Computer Science, and a PhD in Linguistics — and has had a corresponding series of careers — waitressing, software engineering, grammar-writing, assistant professor, and archivist. Writing fiction combines her lifelong love of stories and learning.

Award-winning author Anna Castle writes two historical mystery series: the Francis Bacon mysteries and the Professor & Mrs. Moriarty mysteries. She has earned a series of degrees — BA in the Classics, MS in Computer Science, and a PhD in Linguistics — and has had a corresponding series of careers — waitressing, software engineering, grammar-writing, assistant professor, and archivist. Writing fiction combines her lifelong love of stories and learning.

Website | Blog | Facebook | Twitter | Email

Editor’s note: For more on the contraception available in this period, check out this post on 17th century condoms. They were more of a protection against syphilis, and not a very effective one at that…

Thanks for having me on your blog, Jessica!

LikeLike

Thank you so much for stopping by! This book sounds terrific. I will definitely be reading it! 🙂

LikeLike

Reblogged this on spiritofnlm.

LikeLike

[…] Source: Review: Homosexuality in Renaissance England by Alan Bray […]

LikeLike

Youre so cool! I dont suppose Ive read anything like this before. So good to search out anyone with some original thoughts on this subject. realy thank you for starting this up. this website is something that’s wanted on the internet, someone with a bit originality. useful job for bringing something new to the web!

LikeLike