No dirty, sexy history would be complete without the story of the extraordinary Theresa Berkley, who as a brothel madam and splendid businesswoman to boot, amassed a fortune and compiled a list of London’s finest and their sexual predilections during her long career which spanned both the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries.

She began her business life as a brothel mistress in the late eighteenth century when she opened the first of her premises to patrons who wished to be flogged or birched or do the same, if they preferred a more active role, to the establishment’s willing ladies. It was a time of licentiousness and debauchery which flourished beneath a veneer of high morality and ideals. The service she supplied was not a unique one; flagellation or le vice anglais had played a fairly prominent role in English sex work from about 1700 onwards. She was simply clever and intuitive in how she reacted to and serviced her clientele.

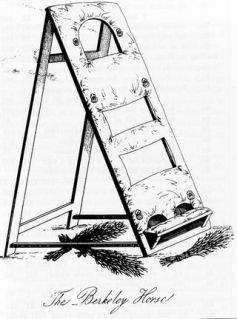

Theresa’s career spanned 49 years, ending only upon her death in 1836. She began in 1787 by turning the White House, a mansion in Soho Square, into a haven of sadomasochism by installing various instruments of torture. These included whip-thongs, cats-o’-nine-tails studded with needle points, supple switches, thin leather straps, curry combs, ox hide straps studded with nails and green nettles. She opened another establishment in 1828 at 28 Charlotte Street (now 84-94 Hallam Street) Fitzrovia which housed a contraption devised for flogging gentlemen known as ‘the Horse’ and where George IV was reputedly a regular visitor (see below).

Berkley brought her collection of instruments of torture with her to Charlotte Street and according to Mary Wilson, another madam, “were more numerous than those of any other governess. Her supply of birch was extensive, and kept in water so it was always green and pliant. There were holly brushes, furze brushes and prickly evergreen called butcher’s brush.” Clients could be “birched, whipped, fustigated, scourged, needle-pricked, half hung, holly brushed, furze brushed, butcher brushed, stinging nettled, curry combed, phlebotomised and tortured.” She had a ready supply of mistresses in the form of Miss Ring, Hannah Jones, Sally Taylor, One-eyed Peg, Bauld-cunted Poll and a black girl called Ebony Bet, who both administered and received floggings and flagellation.

Theresa herself, possessed of a pleasant disposition and whose countenance was pleasing to the eye, occasionally allowed herself, if the price was right, to be whipped by her clients, although she preferred to be the one to administer her flagellations. Political and public figures, together with the wealthy constituted her clientele and she maintained absolute privacy, although the calibre of her clients incited little fear of imprisonment or transportation as had befallen other brothel keepers of the time. Certainly her establishments were never raided by the constabulary.

Berkley was also a devout Christian, her occupation notwithstanding. An insight into her extraordinary professional success is recorded by her erstwhile colleague Mary Wilson, who in the Foreword to The Venus School-Mistress in 1810 wrote that Theresa possessed:

“(That) first grand requisite of a courtesan, viz. lewdness: for without a woman is positively lecherous, she cannot keep up long the affection of it, and will be soon perceived that she only moves her hands or her buttocks to the tune of pounds, shillings and pence. She could assume great urbanity and good humour; she would study every lech, whim, caprice and desire of the customer, and had she the disposition to gratify them, her avarice was rewarded in return.”

Thus Theresa displayed a genuine open-mindedness; an attitude of libertinism which she exploited for financial gain. Her ‘governessing,’ as it was known during the period, brought her wealth, which when she died, was inherited by her brother. He arrived from Australia, where he had been a missionary for 30 years, to find she had left him a large estate. Appalled upon finding how it had been amassed, he immediately renounced all claim as her heir and departed again for the Antipodes.

Henry Ashbee, businessman and erotic author, makes mention of Theresa after her death in his series of Curious and Uncommon Books, published in 1877. He details that Dr. Vance, her medical practitioner and executor “came into possession of her correspondence, several boxes full, which, I am assured by one who examined it, was of the most extraordinary character, containing letters from the highest personages, male and female, in the land.” But he records, “The whole was eventually destroyed” as upon her brother’s renunciation, her estate had devolved to Dr. Vance who similarly wanted nothing to do with it. Thus, the Berkley Whipping Horse, now owned by the Royal Society of Arts in London, together with the rest of the estate became the property of the Crown.

Dr. Vance died while Ashbee was writing his Bibliography of Forbidden Books and Ashbee expressed the hope that perhaps now Theresa’s memoirs, reputedly ready for publication, and which contained “Anecdotes of many of the present Nobility and others, devoted to erotic pleasures and Plates” could be published.

It appears not. Either Dr. Vance or his executors felt this manuscript was too incriminating or too unworthy for public release and it too was destroyed. Such reticence in matters of sex, or prurience, was emblematic of the Victorian age – respectability was the order of the day and the absolutes of godliness, goodness and virtue were what Victorians aspired to achieve, at least outwardly. Concentration on these matters inevitably led to the submersion of the baser instincts and enterprising women like Theresa Berkley, willing to supply services of a sexual and masochistic nature, were able to continue to ply their trade to a willing and receptive clientele.

Not surprising, really, in an era when women were not allowed to own property and could not vote. The sense of power afforded when a woman was able to use a whip on a man for payment would be one difficult to pass up if you were so restricted in life and in achieving an acceptable standard of living. Theresa Berkley was in fact a very dangerous woman; she held the power to blackmail or expose those of high political status and influence, but chose to keep their identities secret during her long career, all the while diarising their proclivities for future reference. One can only conclude she was also a very shrewd woman – one who turned her lewd capabilities into a viable business, one who knew how to survive and prosper in an era when few women were able to do so without inherited wealth and status – and write her memoirs for publication only after her death.* A pity her trustees were not so brave as she in this regard; the truth as she proposed to tell it was thus lost together with a valuable insight into the psyche of the upper class English of the late eighteenth and nineteenth centuries.

*Debate persists over whether Theresa Berkeley wrote and perhaps funded the publication of the 1830 pornographic novel Exhibition of Female Flagellants.

Sources

Linnane, Fergus. Madams: Bawds & Brothel Keepers of London. The History Press, 24 October 2011.

Mudge, Bradford Keyes. The Whore’s Story: Women, Pornography & the British Novel, 1684 – 1830. Oxford University Press, 2000.

Nomis, Anne O. The History & Arts of the Dominatrix. Anna Nomis Ltd. 2013.

Reyes, Heather (Ed). London. Oxygen Books, 2011.

Teardrop, Destiny. Femdom Pioneer Theresa Berkley. Femdom Magazine, Issue 15, 25 April 2011.

Wilson, Mary (Forward). Venus School-Mistress or Birchen Sports, 1810. (first published 1777, reprinted regularly and expanded throughout the nineteenth century)

Manor House, Photo. Nancy – Own work, CC BY-SA 3.0

Leigh Denton studied English Literature and Fine Art before becoming a litigation lawyer in Sydney. She maintains an interest in Victorian and Edwardian history, blogs on this subject at downstairscook.blogspot.com and is presently at work on a novel set in the nineteenth century.

Leigh Denton studied English Literature and Fine Art before becoming a litigation lawyer in Sydney. She maintains an interest in Victorian and Edwardian history, blogs on this subject at downstairscook.blogspot.com and is presently at work on a novel set in the nineteenth century.

She has previously written on the legal and social reformer Josephine Butler for the Dangerous Women Project, an initiative of the Institute for Advanced Studies in the Humanities at the University of Edinburgh and regularly tweets snippets of interest on Twitter as @DownstairsCook.

Victorians, they’re always hiding something of importance from the future.

LikeLiked by 1 person

LOL! I like that. 😉

LikeLike

That is a great piece! Thanks for posting it.

LikeLike

Thanks, David! So glad you enjoyed! 🙂

LikeLiked by 1 person

Time for a screenplay?

LikeLike

[…] choices were obvious, like Victorian dominatrix Theresa Berkley or martyred pagan mathematician Hypatia. Others nominees came as a surprise, like revolutionary […]

LikeLike

[…] Spanking Bank ähnelt einem Sägebock mit gepolstertem Oberteil und Ringen für Fessel. Frau Theresa Berkley, eine britische Domina aus dem 19. Jahrhundert, wurde berühmt für ihre Erfindung des Berkley […]

LikeLike

[…] till 50 shades of Grey, know the origine of BdsmTomb of the FloggingBrief history of the DominatrixTheresa Berkley, Queen of the FlagellantsVintage Fetish […]

LikeLike

[…] – Berkley Horse https://alchetron.com/Berkley-Horse Wikiwand – Theresa Berkley DirtySexHistory – Theresa Berkley Queen of … Etliche digitalisierte und nicht digitalisierte Lexika unter anderem Wikipedia deutsch und […]

LikeLike