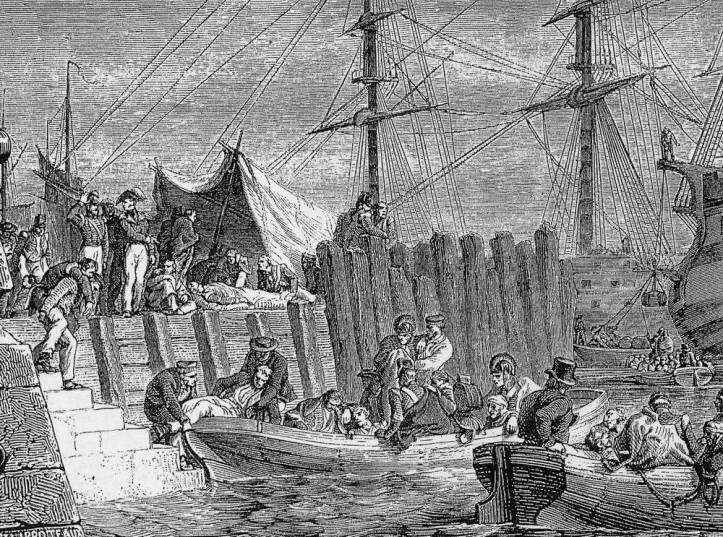

In 1809, the British government sent an amphibious force of 40,000 men and 600 naval vessels to the Scheldt to destroy the French fleet and dockyards at Antwerp and Flushing. It was Britain’s biggest expeditionary undertaking since the beginning of the wars with France in 1793, part of the War of the Fifth Coalition and a diversion to assist the Austrians against Napoleon in central Europe.

The expedition, under the military command of John Pitt, 2nd Earl of Chatham, was a complete failure. The Austrian allies were defeated before the expedition left; although the British captured the island of Walcheren, they advanced too slowly across the neighbouring island of South Beveland, allowing the French to reinforce Antwerp. The expedition was finally withdrawn after a catastrophic outbreak of ‘Walcheren fever’, a combination of several diseases, including malaria.

The impact of this sickness can best be gauged through dry statistics. Of the 39,219 rank and file sent to Walcheren, 11,296 of them were on the sick lists by February 1810. By this time 3,960 were dead. A further 106 had died in battle, but those numbers were swallowed up in the sheer scale of the tragedy.

‘Walcheren fever’ struck the troops suddenly and savagely. One source, the anonymous Letters from Flushing, recorded fatalities from sickness as early as 12 August 1809, but on 8 August the British Chief of Staff reported ‘We have as yet no sick,’ and on 11 August the commander-in-chief Lord Chatham thought ‘the Troops upon ye whole continue healthy.’[1]

By 20 August, however, things had changed. The official Proceedings of the Army recorded on 22 August: ‘Sickness began to show itself among the Troops in South Beveland. On the 20th the number of Sick was 1564, and within the two following days it increased very considerably.’ The next day, the 23rd, the Proceedings recorded ‘Sickness increased very much within the last 24 hours.’ By the 24th the sickness had spread to Walcheren.[2]

At first the officers were not too worried. One of the aides-de-camp to Sir Eyre Coote (Chatham’s second-in-command) recorded in his diary on 24 August: ‘5000 French Troops are said to have fallen a victim to the climate last year, but I consider this as a very exaggerated statement, and at any rate, the constitutions of our men & their habits of life, are much better adapted to this moist atmosphere.’[3]

But by the 27th there were 3467 sick. The following day the officer compiling the official returns could not restrain his concern: ‘The sickness increased to an alarming Proportion, some of the General, and many other Officers were seized with fever, and the Number of Men on the Sick List was nearly 4000.’[4]

The sickness was described by Lieutenant William Keep of the 81st:

The disease comes on with a cold shivering, so great that the patient feels no benefit from the clothes piled upon him in bed, but continues to shiver still, as if enclosed in ice, the teeth chattering and cheeks blanched. This lasts some time and is followed by the opposite extremes of heat, so that the pulse rises to 100 in a small space. The face is then flushed and eyes dilated, but with little thirst. It subsides and then is succeeded by another paroxysm, and so on until the patient’s strength is quite reduced and he sinks into the arms of death.[5]

The British army had been sent to Walcheren with medical supplies for only 30,000 men. It was caught completely off-guard by the scale of the sickness. Things were not helped by the fact that the British had bombarded one of Walcheren’s largest merchant towns, Vlissingen (Flushing), in mid-August, which restricted the accommodation available to the British troops. By 30 August there were nearly 900 sick in Flushing alone, ‘all of them laying [sic] on the bare boards without Paillasses & many without Blankets.’ Two days later Coote’s aide concluded in despair: ‘This island is a mere Hospital and an Inspector of Hospitals will shortly be a more useful officer than the General Commanding.’[6]

All these circumstances contributed to an atmosphere of near-panic. Nobody knew who would be next, and no rank was exempt. ‘A considerable degree of apprehension of Climate and Disease has prevail’d too generally, and there has been much anxiety shewn to get away from this Island as if it had been a second St Domingo,’ the Chief of Staff reported disapprovingly, but by this time several generals (including General Mackenzie-Fraser, who later died) were dropping like flies.[7] By mid-September the Adjutant-General of the army was sending in daily (rather than weekly) sick reports, and Chatham decided to start sending the sick home ahead of official orders from the War Office.

According to one account, one doctor ‘and his assistant [had] nearly five hundred patients prostrate at the same moment … the whole concern was completely floored’. [8] By 23 September the army had almost completely run out of bark (now quinine, used to treat malaria) and the medical corps were of course also losing staff to sickness. Sir Eyre Coote (who took over from Chatham, who was recalled) reported to the Secretary of State for War: ‘I can assure Your Lordship, without any Fear of Exaggeration … that the Situation of the Troops in this Island is deplorable … The Sick are so crowded, as to lay Two in one Bed in several Places, and have no Circulation of Air.’ In Flushing, by contrast, many of these places had rather too much air circulation, owing to ‘the damaged State of the Roofs, never repaired since the Siege.’[9]

Totally overburdened, the medical corps became desperate in their attempts to stem the disease. They had no idea what was causing it: they knew it wasn’t contagious, but thought it was due to ‘local or endemic Causes, viz. the Miasmata or Exhalations from the Soil.’ They did, however, notice that the sailors on board the British ships remained healthy, with the exception of the ones who had gone ashore to help with the siege of Flushing (naturally, as mosquitoes do not breed around salt water). One proposed treatment therefore was to pack the British sick into ships and sail them around the islands, in the hope that the sea air and a change of scene would restore them to health. Unsurprisingly, this did not work.[10]

The impact of Walcheren fever on the British army was significant and long-lasting. The soldiers who had served on the campaign continued to relapse periodically for years after. In March 1812 Lord Wellington, in the midst of fighting in the Spanish Peninsula, lamented the fact that his troops had been ‘so much shaken by Walcheren.’ [11] The careers of the commander-in-chief of the Army, Lord Chatham, and the naval commander, Sir Richard Strachan, were destroyed by the disaster.

The British government that had planned the expedition under the Duke of Portland fell, and its successor nearly foundered during the ensuing parliamentary inquiry into the debacle. Two government ministers, Lord Castlereagh and George Canning, ended up fighting a duel. None of this, of course, was especially comforting to the four thousand men who had died from ‘Walcheren fever’.

References

[1] Letters from Flushing … by an Officer of the Eighty-First Regiment (London, 1809), p. 120; Sir Robert Brownrigg to Colonel Gordon, 8 August 1809, BL Add MSS 49505, f. 9; Chatham to Castlereagh, 11 August 1809, PRONI D3030/3220; John Webb to the Surgeon General, 27 August 1809, A Collection of Papers relating to the Expedition to the Scheldt (London, 1809), pp. 588-90.

[2] The National Archives WO 190, 22-4 August 1809.

[3] University of Michigan Coote MSS, Box 29/3, Diary of the Walcheren Expedition, 24 August 1809.

[4] The National Archives WO 190, 27-8 August 1809.

[5] Quoted by Martin Howard, Walcheren 1809, Barnsley, 2011, p. 161.

[6] University of Michigan Coote MSS, Box 29/3, Diary of the Walcheren Expedition, 30 August, 1 September 1809.

[7] Sir Robert Brownrigg to Colonel Gordon, 8 September 1809, BL Add MSS 49505 f. 69.

[8] Rifleman Harris, quoted by Howard, Walcheren 1809, p. 172.

[9] Sir Eyre Coote to Castlereagh, 17 September 1809, A Collection of Papers, pp. 137-40.

[10] Memorandum dated 25 September 1809, A Collection of Papers, pp. 623-5; Sir Eyre Coote to Lord Liverpool, 23 October 1809, A Collection of Papers, pp.177-8.

[11] Howard, Walcheren 1809. p. 215.

Further reading

Gordon Bond, The Grand Expedition (Athens, GA, 1971)

Martin R. Howard, Walcheren 1809 (Barnsley, 2011)

John Lynch, ‘The Lessons of Walcheren Fever, 1809’, Military Medicine 174(3) 2009, pp. 315-19

T.H. McGuffie, ‘The Walcheren Expedition and the Walcheren Fever’, English Historical Review  62(243) 1947, pp. 191-202

62(243) 1947, pp. 191-202

Jacqueline Reiter has a PhD in late 18th century political history from the University of Cambridge. A professional librarian, she lives in Cambridge with her husband and two children. She blogs at www.thelatelord.com and you can follow her on Facebook or Twitter. Her first book, The Late Lord: the life of John Pitt, 2nd Earl of Chatham, was published by Pen & Sword Books in January 2017.

Oddly, I saw the map and headline and new instantly who wrote it! Well done Jacqueline.

LikeLike

Pahahaha! *owns it*

Thank you!

LikeLiked by 1 person

“as mosquitoes do not breed around salt water”.

Some do ‘Particularly annoying to the troops were the unexpected swarms of mosquitoes, which bit them until their faces swelled’.

Walcheren fever was not a newly discovered killer disease but a lethal combination of old diseases—malaria, typhus, typhoid, and dysentery—acting together in a group of men already debilitated by previous campaigning. See here: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1127097/

LikeLike

That’s fascinating, Fred. Thanks for the link!

LikeLike

Indeed, as I acknowledge in the second paragraph. McGuffie was probably the first to identify this in 1947, and Howard (whose book I highly recommend) went into some detail explaining why the combination was so especially lethal to the British.

It is nevertheless true that the epidemic did not affect the sailors, with the exception of those who spent considerable time ashore.

LikeLiked by 2 people