When people find out that I wrote the non-fiction companion to Mercy Street, the PBS series set in a Union hospital during the American Civil War, they almost always ask me whether the show gets the historical details right. Particularly whether the medicine is accurate. I tell them that the series does a great job with historical accuracy with one exception: the television version of Mansion House Hospital isn’t dirty enough.

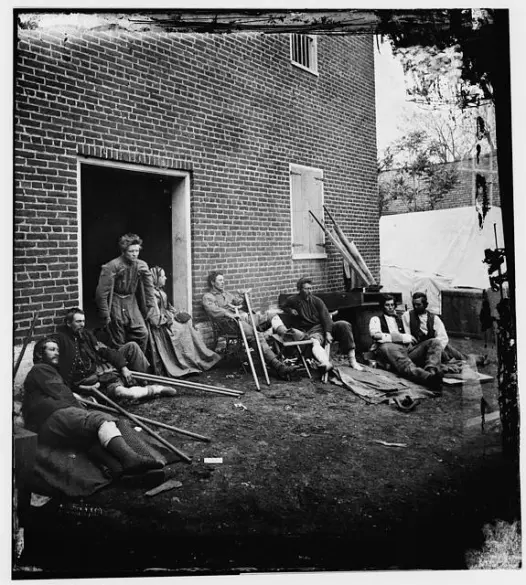

Today we think of hospitals as bastions of sanitation. But in the mid-19th century hospitals were dangerous, dirty, smelly places that many people rightly regarded as death traps. Add in the chaos of war and you had breeding grounds for contagious diseases, including smallpox, measles, pneumonia, influenza, tuberculosis, typhoid and yellow fever.

At the beginning of the war, the Union Army had a few hospitals attached to forts in the west, but none along the eastern seaboard. In order to cope with the crisis of illness and injury that began before the first battle was fought, the Army’s Medical Bureau requisitioned buildings for use as general hospitals throughout Washington DC and surrounding towns, primarily hotels and schools. Many of them were run down and most suffered from inadequate ventilation and poorly designed toilet facilities, which aggravated the problems of disease.

The largest of the Washington hospitals was the Union Hotel, where Louisa May Alcott served as a nurse for a little over a month. The hospital opened on May 25, 1861, and was soon infamous for its poor condition and worse smells. A report on its condition, made shortly after the first Battle of Bull Run in July 1861, stated that

…the building is old, out of repair, and cut up into a number of small rooms, with windows too small and few in number to afford good ventilation. Its halls and passages are narrow, tortuous and abrupt…There are no provisions for bathing, the water-closets and sinks are insufficient and defective and there is no dead-house [a room or structure where dead bodies could be stored before burial or transportation—a grim necessity in a Civil War hospital.] The wards are many of them overcrowded and destitute of arrangements for artificial ventilation. The cellars…are damp and undrained and much of the wood is actively decaying. (1)

Alcott was more blunt. In a letter home, she complained “a more perfect, pestilence-box than this house I never saw,–cold, damp, dirty, full of vile odors from wounds, kitchens, wash-rooms, and stables.”

Nurses, supported by convalescent soldiers, occasional chambermaids, and an army of laundresses, fought to keep hospitals clean in the face of a seemingly endless stream of mud, blood, and diarrhea—a common element of Civil War military life seldom mentioned in letters and memoirs of the period. (An average of 78 percent of the Union Army suffered from what they called the “Tennessee quick-step” at some point each year.) It was a monumental task, even by standards of cleanliness that required patients’ undergarments to be changed once a week and saw nothing wrong with reusing lightly soiled bandages.

Keeping a supply of clean shirts, clean underwear, clean sheets, and clean bandages required a heroic effort—especially when a given patient might require three clean bandages and a fresh shirt daily, all of which would need to be thrown away because they were so stained with blood and pus. The newly constructed general hospital at Portsmouth Grove, Rhode Island, reported boasted a new-fangled steam washing machine that could wash and mangle four thousand pieces of laundry a day. It was an innovation that hospitals improvised from hotels and schools could only dream of with envy. Most hospitals had to make do with wooden washtubs, soap-sized kettle for heating water, and elbow grease. Washable clothing, bed linens, bandages and rags were washed in hot water using soft soap and a scrub board, boiled to kill lice and insects, rinsed several times in hot water, allowed to cool, and then rinsed again in cool water. Water had to be carried by hand from water sources that varied in degree of inconvenience. Once acquired, water was heated in large kettles on wood- or coal-burning stoves and carried from kitchen to washtub. It was not unusual for a general hospital laundry to process two or three thousand pieces of laundry in one day.

Even the best efforts to keep hospitals clean did not deal with the root causes of contagion. A bacterial theory of disease was some decades in the future. The prevailing medical theory of the period focused on clean air rather than clean water because doctors believed that diseases were spread through the poisoned atmosphere of “miasmas.” Doctors interested in hospital sanitation were concerned with eradicating foul smells. New hospitals were built with an eye toward providing fresh air. Hospital designers would have been well advised to focus on handling human waste instead.

The sanitary arrangements in Civil War hospitals made it easy for diseases linked to contaminated water, like typhoid and dysentery, to spread. Many latrines and indoor water closets had to be flushed by hand, carried by hand from a water source some distance away. As a result, they were not flushed out as frequently as required to keep them sanitary. Worse, in some hospitals, latrines were located too close to the kitchens. Even when there was an adequate distance between the two, flies carried bacteria on their feet as they flew between latrines, kitchens and patients’ dinner trays.

It’s no wonder that disease was responsible for two-thirds of all Civil War deaths.

(1) Quoted in Hannah Ropes. Civil War Nurse: The Diary and Letters of Hannah Ropes, ed. John R. Brumgardt. (Knoxville: University of Tennessee Press, 1980) p. 40.

(2) Quoted in Ropes, p. 40

Further Reading

Humphreys, Margaret. Marrow of Tragedy: The Health Crisis of the American Civil War. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press. 2013

Rutkow, Ira. M. Bleeding Blue and Gray: Civil War Surgery and the Evolution of American Medicine. New York: Random House. 2005.

Schultz, Jane E. Women at the Front: Hospital Workers in Civil War America. Chapel Hill and  London: University of North Carolina Press. 2004.

London: University of North Carolina Press. 2004.

Pamela D. Toler is a freelance writer with a PhD in history and a large bump of curiosity. She is the author of Heroines of Mercy Street: The Real Nurses of the Civil War and is currently writing a global history of women warriors, with the imaginative working title of Women Warriors. She blogs about history, writing, and writing about history at History in the Margins.

And there were the care givers. Walt Whitman recorded on two consecutive days deaths from “overdose on opium pills and laudanum from an ignorant ward master” and a soldier who received “inwardly” (internally) “an ammonia solution intended as a foot bath”

Walt kept himself clean, considering a bath and fresh clothes part of his healing ritual for the men he visited.

(Excerpt From: Huets, Jean. “With Walt Whitman: Himself.” v4.1. Circling Rivers, 2015. iBooks. Check out this book on the iBooks Store: https://itun.es/us/5GBw8.l)

LikeLiked by 1 person

I took a walking ghost tour of Gettysburg and one of the places we visited was a hospital at the time of the battle – the solemness lent itself to the imagination and I could visualize the mangled limbs piling up outside the building.

LikeLike

[…] and impatient for the show to go on, they had a right to be, since hospitals had long been notorious deathtraps. But both the familiarity of the format and the demonstrable improvements made to hospitals over […]

LikeLike

[…] and impatient for the show to go on, they had a right to be, since hospitals had long been notorious deathtraps. But both the familiarity of the format and the demonstrable improvements made to hospitals over […]

LikeLike

[…] and impatient for the show to go on, they had a right to be, since hospitals had long been notorious deathtraps. But both the familiarity of the format and the demonstrable improvements made to hospitals over […]

LikeLike

[…] and impatient for the show to go on, they had a right to be, since hospitals had long been notorious deathtraps. But both the familiarity of the format and the demonstrable improvements made to hospitals over […]

LikeLike

[…] and impatient for the show to go on, they had a right to be, since hospitals had long been notorious deathtraps. But both the familiarity of the format and the demonstrable improvements made to hospitals over […]

LikeLike

[…] and impatient for the show to go on, they had a right to be, since hospitals had long been notorious deathtraps. But both the familiarity of the format and the demonstrable improvements made to hospitals over […]

LikeLike

[…] and impatient for the show to go on, they had a right to be, since hospitals had long been notorious deathtraps. But both the familiarity of the format and the demonstrable improvements made to hospitals over […]

LikeLike

[…] تو ان کو ہونے کا حق تھا ، چونکہ ہسپتالوں کو طویل عرصے سے بدنام زمانہ موت کا جال. لیکن فارمیٹ سے واقفیت اور اس عرصے کے دوران ہسپتالوں […]

LikeLike

[…] and impatient for the show to go on, they had a right to be, since hospitals had long been notorious deathtraps. But both the familiarity of the format and the demonstrable improvements made to hospitals over […]

LikeLike

[…] and impatient for the show to go on, they had a right to be, since hospitals had long been notorious deathtraps. But both the familiarity of the format and the demonstrable improvements made to hospitals over […]

LikeLike