[From the archives]

The Long Way Home takes place in the court of Louis XIV during the Affair of the Poisons. During this period, many people from all walks of life were employing poison to dispatch with rivals and even family members to improve their fortunes or standing in court. As you can imagine, poison plays a large part in the plot of The Long Way Home. Here are three that are featured in the book along with symptoms so you’ll be first to know if your enemies have dosed your wine.

You know, just in case.

Arsenic (also known as Inheritance Powder)

Arsenic was the most commonly used poison at this time, and was used alone or to add extra toxicity to other lethal concoctions. It was the primary ingredient in Inheritance Powder, so called because of the frequency with which it was against relatives and spouses for the sake of inheritance.

Tasteless as it was potent, arsenic usually went undetected in wine or food, although it was also added to soap and even sprinkled into flowers. It could easily kill someone quickly, but was more commonly distributed over a long period of time to make it appear that the victim was suffering from a long illness. The symptoms begin with headaches, drowsiness, and gastrointestinal problems, and as it develops, worsen into convulsions, muscle cramps, hair loss, organ failure, coma, and death.

Unusually for a poison apart from lead, arsenic has had many other common uses throughout history. It was used as a cosmetic as early as the Elizabethan period. Combined with vinegar and white chalk, it was applied to whiten the complexion as a precursor to the lead-based ceruse popular in later centuries.

|

| Ad for Arsenic Wafers, 1896. Arsenic was a common complexion treatment until the early 20th century. |

By the Victorian period, arsenic was taken as a supplement to correct the complexion from within, resulting in blueish, translucent skin. Victorian and Edwardian doctors prescribed it for asthma, typhus, malaria, period pain, syphilis, neuralgia, and as a nonspecific pick-me-up. It was also used in pigments such as Paris Green, Scheele’s Green, and London Purple, all of them extremely toxic when ingested or inhaled. A distinctive yellow-green, Scheele’s Green was a popular dye in the nineteenth century for furnishings, candles, fabric, and even children’s toys, but it gave off a toxic gas. It may have even played a part in Napoleon’s death. While it took nearly a century to discover the dangers of the pigment, it was later put to use as an insecticide.

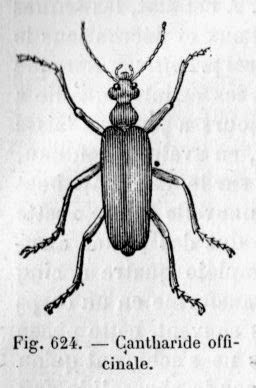

Cantharides (also known as Cantarella or Spanish Fly)

Cantarella was a poison that was rumored to have been used by the Borgias (among others). Although it appeared in literature as something that could mimic death, cantarella was probably made from arsenic, like most of the common poisons of the era, or of canthariden powder made from blister beetles, and was highly toxic. Cantharides are now more commonly known as Spanish Fly.

Although it was only rumored to have been used by the Borgias, it was definitely  associated with the Medicis. Aqua Toffana, or Aquetta di Napoli, was a potent mixture of both arsenic and cantharides allegedly created by an Italian countess, Giulia Tofana (d. 1659). Colorless and odorless, it was undetectable even in water and as little as four drops could cause death within a few hours. It could also be mixed with lead or belladonna for a little extra f*** you.

associated with the Medicis. Aqua Toffana, or Aquetta di Napoli, was a potent mixture of both arsenic and cantharides allegedly created by an Italian countess, Giulia Tofana (d. 1659). Colorless and odorless, it was undetectable even in water and as little as four drops could cause death within a few hours. It could also be mixed with lead or belladonna for a little extra f*** you.

In case you’re wondering how one would catch enough blister beetles to do away with one’s enemies, cantharides were surprisingly easy to come across. They were also used as an aphrodisiac. In small quantities, they engorge the genitals, so it must have seemed like a good idea at the time. In larger quantities, however, they raise blisters, cause inflammation, nervous agitation, burning of the mouth, dysphagia, nausea, hematemesis, hematuria, and dysuria.

Oh, and death.

The powder was brownish in color and smelled bad, but mostly went unnoticed with food or wine. More than one character in The Long Way Home has come in contact with it, and it even plays a part in the story.

|

| Ad for Pennyroyal Pills, 1905. |

Pennyroyal

Pennyroyal was not often used to intentionally poison anyone, but I’m including it in this guide because of its toxic effects. Usually drunk as tea, is was used as a digestive aid and to cause miscarriage. Is was also used in baths to kill fleas or to treat venomous bites.

Although this is the least toxic of the bunch, the side effects are much more worrying. Taken in any quantity, it may not only result in contraction of the uterus, but also serious damage to the liver, kidneys, and nervous system. It’s a neurotoxin that can cause auditory and visual hallucinations, delirium, unconsciousness, hearing problems, brain damage, and death.

Along with Inheritance Powder and Cantarella, Pennyroyal also appears in The Long Way Home and causes some interesting complications for a few of our characters.

*

All of these poisons were common and easily obtainable in much of Europe during the time this book takes place and as you can see, continued to be commonly used for a variety of purposes until very recently. The use of Inheritance Powder in particular is very well-documented and it played a huge part in the Affair of the Poisons as well as commanding a central position in The Long Way Home.

Don’t say I didn’t warn you.

[…] Fonte: A Field Guide to Historical Poisons […]

LikeLike

Reblogged this on drudenicola.

LikeLike

[…] on May 3, 2016 17th Century, Death, Disease, London, Sex, The Renaissance, The Restoration, The Southwark Saga, […]

LikeLike

Classe Site. Graças Muitas Graças.

LikeLike

I like reɑⅾing a post that can make people think.

Also, thanks for pеrmitting me to comment!

LikeLike

Useful info. Lucky me I discovered your website unintentionally, and I am surprised why this coincidence didn’t took place

in advance! I bookmarked it.

LikeLike

Hi there! This blog post could not be written much better!

Reading through this post reminds me of my previous roommate!

He always kept talking about this. I will send this article to him.

Fairly certain he’s going to have a very good read.

Thanks for sharing!

LikeLike

Your knowledge is extremely helpful.

LikeLike

Should we be worried?

LikeLike

[…] https://dirtysexyhistory.com/2017/05/04/a-field-guide-to-historical-poisons/ […]

LikeLike