Centuries of nostalgic medievalism have given us some funny ideas about sexuality in the Middle Ages. We know religion ruled, no one married for love, and sex was for procreation only…right?

Not so much. When studying the Middle Ages, you need to consider the sources. Every author had a bias and could only write what they saw. Most of our modern ideas about sexuality come from Canon Law, but people did not obey all of the laws of the Church in the Middle Ages any more than they do today. To get a better idea of what life was really like, we have to draw on other sources as well.

Today we’re going to jump into the deep end with medieval contraception and abortion. The popular assumption is that contraception did not exist and abortion must have been a serious crime, if it happened at all. The issue with this argument is that we take for granted that they must have had a similar understanding of pregnancy and a greater sense of religious morality when it came to the issue of contraception and abortion. To get to the bottom of this, we have to throw out these assumptions and start at the beginning.

Sex

Fornication was still a sin, but it was one most were guilty of. When primogeniture became the rule in the eleventh century, it created a whole class of people were unlikely to ever marry. Noble families with multiple children could only pass on their property to the eldest. The rest of the children would remain in the household even as adults until they married other property-holding people or until circumstances changed. Many entered the Church, where marriage and concubinage among the clergy was still common until the twelfth century. Wealthy families might equip younger sons as knights. Knights could not be expected to marry until they inherited property or came by it through other means; most younger sons never married at all. As for daughters, the pool of landed noblemen to marry was pathetically small. With larger families and fewer opportunities for marriage, much of the nobility never married. To assume they all remained celibate in a culture that all but deified love and had a popular handbook for conducting romantic, sexual, and frequently extramarital relationships is naïve at best. (1)

As for the lower classes, marriage was almost a fluid concept. It was common for people to marry in secret, and these marriages were every bit as valid as any performed outside a church. According to Gratian’s Decretum, all it took to make a marriage legal was three things: love, sex, and consent. As long as the love and consent were there, sexual relationships including those with concubines could be considered informal marriages.

Because the line between fornication and legal marriage was a bit blurry, fornication was more or less accepted in practice. Who’s to say the consenting couple did not marry in secret? Many penitentials appearing during and after the twelfth century classified sex outside of marriage as only a minor sin. Members of the Synod of Angers in 1217 stated unequivocally that they personally knew many confessors who gave no penance for it at all. In practice, the Church tolerated fornication as long as there was no adultery being committed.

Prostitution was legal and common. Although the Church did not condone it, this did not stop it from regulating and profiting from it (see Prostitution and the Church in Medieval Southwark). After all, someone had to see to the needs of the scores of unmarried men and those who had entered the Church out of necessity rather than desire. The Church viewed prostitution as a necessary evil. While active sex workers could not be viewed as respectable members of society, they nevertheless performed an important public service.

Outside of the Church, many medieval writers, such as Albertus Magnus and Constantine the African, viewed sex as a crucial component to overall health on equal footing with food, sleep, and exercise. Sexual release was believed to be the best way to get rid of toxic humors and abstinence could lead to weakness, illness, madness, and death. Sexual enjoyment was necessary for men and women, and was an essential component to conception.

Sex happened. Penitentials were distributed throughout the Church to prescribe penance for every vice we can imagine today (and a fair few we can’t). Troubadours sang about it in their filthy, filthy songs. Pregnancy was inevitable and dangerous. So how did they deal with it?

Menstrual Regulators

It sounds obvious, but people in the Middle Ages did not have the same understanding of pregnancy that we have today. As they could not pinpoint the moment of conception, there was no distinction between the prevention of pregnancy (contraception) and the ending of one (abortion). “Remedies to regulate the menstrual cycle” were common and arguably more widely accepted than they are now. Recipes were recorded in medical texts, shared between women, and they appeared in household handbooks. They could be made at home with a few ingredients most women would recognize.

This ninth century recipe appeared in the Lorsch Manuscript, a medical treatise written by Benedictine monks:

A Cure for All Kinds of Stomach Aches

For women who cannot purge themselves, it moves the menses.

8 oz. white pepper

8 oz. ginger

6 oz. parsley

2 oz. celery seeds

6 oz. caraway

6 oz. spignel seeds

2 oz. fennel

2 oz. geranium/ or, giant fennel

8 oz. cumin

6 oz. anise

6 oz. opium poppy

These recipes did not come out of the blue. There is evidence that similar abortifacients had been used as far back as ancient Egypt. Pepper had been used since the Roman period as a contraceptive, and fennel is related to silphium, the ancient plant farmed to extinction for its contraceptive properties. The other ingredients have been found to have antifertility effects, and the opium was used as a sedative. Other similar recipes were employed throughout the period and beyond; menstrual regulators using the same ingredients continued to be sold as late as the nineteenth century.

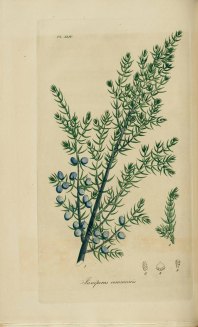

In addition to those mentioned above, artemisa and juniper were both known to inhibit fertility. Artemisia is a genus of plant in the daisy family asteraceae. There are more than two hundred types of artemisia, among them mugwort, tarragon, and wormwood, the key ingredient in absinthe centuries later. In the twelfth century, Trotula recommended artemisia as a “menstrual stimulator” and in the thirteenth century, Arnald of Villanova advised taking it with capers for maximum efficacy. Modern medicine has confirmed its use: artemisia inhibits estrogen production and can prevent ovulation much like pharmaceutical contraceptives today.

Artemisia was not without its side effects. Wormwood is a notorious toxin known to cause hallucinations and changes in consciousness. Ingested in large quantities, it can cause seizures and kidney failure. (2)

Juniper had been used as a contraceptive since the Roman period. Pliny the Elder recommended rubbing crushed juniper berries on the penis before sex to prevent conception. Its popularity continued throughout the Middle Ages; Arabic medical writers Rhazes, Serapion the Elder, and ibn Sina all list it as an abortifacient, and this knowledge was made more readily available throughout Europe when Gerard of Cremona translated their words in the twelfth century. According to ibn Sina, juniper produced an effect very similar to a natural miscarriage, and so it could be employed without detection.

Historian John Riddle argues that all women knew which plants inhibited fertility and how to use them effectively. They were under no illusions as to their purpose. Although most of what we know about medieval contraception and abortion does come from medical texts written by men, they would have come by the information from women who were using it on a regular basis.

Morality

In the ancient world and even the early Christian Church, abortion was not considered immoral. Although it is often interpreted differently today, the medieval church followed the guidelines of the Bible in believing that life began at birth (Genesis 2:7). St. Thomas Aquinas argued that souls are created by God, not by man, and that the soul did not enter the body until the infant drew its first breath.

Abortion or “menstrual regulation” was not explicitly mentioned in the Bible except to recommend it in the case of suspected unfaithful wives (Numbers 5:11-31) (3), and whether or not it was immoral in the Middle Ages depended on who was asked.

Burchard of Worms’ Decretum tackled the issue of abortion in the section titled Concerning Women’s Vices. Burchard unequivocally opposed it, but the penance recommended varied. To Burchard, the severity of the sin was not dependent on the act itself, but the status of the woman and the circumstances of conception. The worst crime was that resulting from adultery. For this he orders seven years of abstinence and a lifetime of “tears and humility.” Abortion stemming from fornication was also bad (penance for ten years on fast days), unless the woman was poor or a sex worker (statistically likely). If the woman was poor and acted because she would not be able to feed a child, it was understandable and no penance was prescribed.

Regardless of the Church’s recommendations, abortion was not actually illegal. In fact, the first law that made abortion illegal in the English-speaking world did not come until the Ellenborough Act of 1803, and even that only outlawed abortions obtained by taking “noxious and destructive substances.” It was not until 1869 that the Catholic Church decided that life began at conception.

Conclusions

If there is one thing we should take away from this, it is that when it came to sex, the Middle Ages were not as different from today as we often assume. People married for love, they had sex for fun, and family planning existed and was used more or less effectively. Due to centuries of literature and art portraying the Middle Ages as an idealized time of chastity and moral superiority, we have come to collectively accept a fiction that bears only a passing resemblance to a much more complicated truth.

Through this Contraception in History series, I have tried to show that although reproduction has been the primary purpose of sex throughout history, it was not the only purpose, and people have always found ways to take their reproductive destinies into their own hands.

Jessica Cale

Sources

Brundage, James. Sex and Canon Law. Garland Reference Library of the Humanities Volume 1696. Issue 1996: Pages 33-50.

Burchard of Worms. Decretum (c. 1008).

Burford, EJ. Bawds and Lodgings, a History of the London Bankside Brothels c. 100-1675. London, Peter Owen, 1976

Cadden, Joan. Western Medicine and Natural Philosophy. Garland Reference Library of the Humanities Volume 1696. Issue 1996: Pages 51-80.

Capellanus, Andreas. The Art of Courtly Love. Translated by John Jay Parry. New York, Columbia University Press, 1960

Gaddesden, John. Rosa anglica practica medicine. Venice, Bonetus Locatellus, 1516.

Gies, Frances and Joseph. Marriage and Family in the Middle Ages. New York, Harper & Row, 1987

Payer, Pierre J. Confession and the Study of Sex in the Middle Ages. Garland Reference Library of the Humanities Volume 1696. Issue 1996: Pages 3-32.

Riddle, John M. Contraception and Early Abortion in the Middle Ages. Garland Reference Library of the Humanities Volume 1696. Issue 1996: Pages 261-274.

Tannahill, Reay. Sex in History. New York, Stein and Day, 1992

1. See The Art of Courtly Love.

2. Fun fact: Nicholas Culpeper claimed that wormwood was the key to understanding his 1651 book The English Physitian. Unlike the rest of the book, the entry for wormwood is a stream-of-consciousness ramble that reads like someone who was ingesting it at the time.

3. It is very possible the bitter waters in this verse refer to wormwood, a notoriously bitter substance known to induce miscarriage.

If you would like to know more about Contraception in History, see below for the rest of the series:

Contraception in History I. Aristotle, Hippocrates, and a Whole Lotta Lead

Contraception in History II. Contraception in Ancient Egypt: Hormonal Birth Control, Pregnancy Tests, and Crocodile Dung.

Contraception in History III. Ancient Birth Control: Silphium and the Origin of the Heart Shape

Contraception in History IV. Minos, Pasiphae, and the Most Metal Euphemism for V.D. Ever

Contraception in History V. “Love’s Pleasing Paths in Blest Security”: Seventeenth Century Condoms

[…] Sex, contraception and abortion in Medieval England. […]

LikeLike

Totally agree with this interesting post. And it makes me happy on behalf of all the women who have gone before me that they knew how to enjoy sex without necessarily ending up with child.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks, Anna! I agree, that’s reassuring to know. A world without contraception is too scary to contemplate.

LikeLike

Great post, Jessica! Helena Kelly mentioned elixirs for “female troubles” and to “improve flow” in Jane Austen: A Secret Radical (in the context of the fear of childbirth that shows up regularly in Austen’s work and life). These were sold not just by apothecaries, but in circulating libraries — which obviously offered a lot of things besides books! — and they were advertised openly in the newspapers. Not the common perception of the late 18th/early 19th century England, either.

LikeLike

That’s so fascinating, Larry! We haven’t had a post on 18th/19th century contraception yet. That sounds like a great place to start! 🙂

LikeLike

Love this! Is there a way to reblog it?

LikeLiked by 1 person

Absolutely! If WordPress doesn’t let you, feel free to repost or link to it. Let me know if I can help 😉

LikeLiked by 1 person

Reblogged & tweeted. Bonus: it also shows up on my Goodreads feed. Thanks!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Reblogged this on History Rocks!.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Nice! Thanks very much! 🙂

LikeLiked by 1 person

Fascinating. I knew that our ancestors were at it like bunnies within certain parameters – the detail, particularly the recipe and the all around that, was unknown to me and really interesting.

LikeLike

Thanks very much! I found it while researching something else, but I was so excited to find a real recipe rather than another vague euphemism that I had to write a post about it. It’s good to know it existed, but I hope no one tries it at home!

LikeLike

Thanks very much! A reality without contraception is too scary to contemplate.

LikeLike

Thanks very much! A domain without contraceptive method is too scarey to study.

LikeLike