In 1811, before anesthesia was invented, Frances Burney d’Arblay had a mastectomy aided by nothing more than a wine cordial. She wrote such a gripping narrative about her illness and operation afterwards readers today still find it riveting and informative.

Fanny came from a large family and was the third child of six. From an early age, she began composing letters and stories, and she became a phenomenal diarist, novelist, and playwright in adulthood. Certainly, her skillful writing was a primary reason her mastectomy narrative had such appeal.

In her narrative, Fanny provides “psychological and anatomical consequences of cancer … [and] while its wealth of detail makes it a significant document in the history of surgical techniques, its intimate confessions and elaborately fictive staging, persona-building, and framing make it likewise a powerful and courageous work of literature in which the imagination confronts and translates the body.” Prior to her surgery, she had written similar works about “physical and mental pain to satirize the cruelty of social behavioral strictures, especially for women.”

Fanny grew up in England and had been embraced by the best of London society. She had served in George III and Queen Charlotte’s court as Second Keeper of the Royal Robes. Moreover, she was admired by such literary figures as Hester Thrale, David Garrick, and Edmund Burke. Fanny also befriended Dr. Samuel Johnson, the English writer who made significant contributions to English literature as a poet, essayist, moralist, literary critic, biographer, editor and lexicographer. In fact, some of Fanny’s best revelations are about Johnson, how he teased her, and the fondness that he held for her.

In 1793, Fanny married Louis XVI Alexandre-Jean-Baptiste Piochard d’Arblay and became Madame d’Arblay. D’Arblay was an artillery officer who served as adjutant-general to the famous hero of the American Revolution, Gilbert du Motier, Marquis de Lafayette. D’Arblay had fled France for England during the Revolution just as had many other Frenchmen. However, in 1801, d’Arblay was offered a position in Napoleon Bonaparte’s government. He and Fanny relocated to France in 1802 and moved to Passy (the same spot where Benjamin Franklin and the princesse de Lamballe had lived), and they remained in France for about ten years.

While living in France, Fanny suffered breast inflammation in her right breast in 1804 and 1806. She initially dismissed the problem but then in 1811 the pain became severe enough that it affected her ability to use her right arm. Her husband became concerned and arranged for her to visit Baron Dominique-Jean Larrey, First Surgeon to the Imperial Guard, as well as the leading French obstetrician, surgeon, and anatomist, Antoine Dubois.

The French doctors treated Fanny palliatively but as there was no response to the treatment, it was determined surgery was necessary. Fanny’s surgery occurred on 11 September 1811. At the time, surgery was still in its infancy and anesthesia unavailable. Cocaine was later isolated, determined to be an effective local anesthetic, and used for the first time in 1859 by Karl Koller. So, it must have been horrific for Fanny to experience the pain of a mastectomy with nothing more than a wine cordial that may have contained some laudanum. Fanny was traumatized by the surgery and it took months before she wrote about the surgery details to her sister Esther exclaiming:

“I knew not, positively, then, the immediate danger, but every thing convinced me danger was hovering about me, & that this experiment could alone save from its jaws. I mounted, therefore, unbidden, the Bed stead – & M. Dubois placed upon the Mattress, & spread a cambric handkerchief upon my face. It was transparent, however, & I saw through it, that the Bed stead was instantly surrounded by the 7 men & my nurse. I refused to be held; but when, Bright through the cambric, I saw the glitter of polished Steel – I closed my Eyes. I would not trust to convulsive fear the sight of the terrible incision. A silence the most profound ensued, which lasted for some minutes, during which, I imagine, they took their orders by signs, & made their examination – Oh what a horrible suspension! … The pause, at length, was broken by Dr. Larry [sic], who in a voice of solemn melancholy, said ‘Qui me tiendra ce sein?”

Fanny went on to describe “torturing pain” and her inability to restrain her cries as the doctors cut “though veins – arteries – flesh – nerves.” Moreover, she noted:

“I began a scream that lasted unintermittingly during the whole time of the incision – & I almost marvel that it rings not in my Ears still! so excruciating was the agony. When the wound was made, & the instrument was withdrawn, the pain seemed undiminished, for the air that suddenly rushed into those delicate parts felt like a mass of minute but sharp & forked poniards, that were tearing the edges of the wound. … I attempted no more to open my Eyes, – they felt as if hermetically shut, and so firmly closed, that the Eyelids seemed indented into my Cheeks. The instrument this second time withdrawn, I concluded the operation over – Oh no! presently the terrible cutting was renewed – and worse than ever … I then felt the Knife rackling against the breast bone – scraping it! – This performed, while I yet remained in utterly speechless torture. “

Despite the excruciating pain, Fanny lived through the operation, and her surgery was deemed a success. Larrey produced a medical report about his brave patient stating that he removed her right breast at 3:45pm and that Fanny showed “un Grand courage.” Courageous as she was, there was no way for doctors to determine if Fanny’s tumor was malignant or if she suffered from mastopathy.

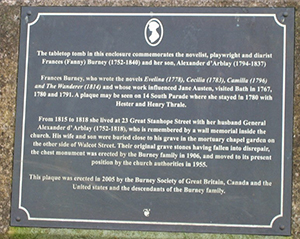

Fanny’s healing took a long time, and while still recuperating, she and husband returned to England in 1812. Six years later, in 1818, her husband died from cancer, and she died twenty-two years later, at the age of eighty-seven, on 6 January 1840 in Lower Grosvenor-street in London. As Fanny had requested, a private funeral was held in Bath, England, and attended by a few relatives and some close friends. She was laid to rest in Walcot Cemetery, next to her beloved husband and her only son Alexander, who had died three years earlier. Their bodies were then moved during redevelopment of the Walcot Cemetery to the Haycombe Cemetery in Bath and are buried beneath the Rockery Garden.

References

DeMaria, Jr., Robert, British Literature 1640-1789, 2016

“Died,” in Northampton Mercury, 18 January 1840

Epstein, Julia L., “Writing the Unspeakable: Fanny Burney’s Mastectomy and the Fictive Body,” in Representations, No. 16 (Autumn, 1986), pp. 131-166

Madame D’Arblay, in Evening Mail, 20 January 1840

Madame D’Arblay’s Diary, in Evening Mail, 18 May 1842

“The Journals and Letters of Fanny Burney (Madame D’Arblay), Volume VI, France 1803-1812,” in Cambridge Journals

Geri Walton has long been interested in history and fascinated by the stories of people from the 1700 and 1800s. This led her to get a degree in History and resulted in her website, geriwalton.com which offers unique history stories from the 1700 and 1800s. Her first book, Marie Antoinette’s Confidante: The Rise and Fall of the Princesse de Lamballe, discusses the French Revolution and looks at the relationship between Marie Antoinette and the Princesse de Lamballe.

Geri Walton has long been interested in history and fascinated by the stories of people from the 1700 and 1800s. This led her to get a degree in History and resulted in her website, geriwalton.com which offers unique history stories from the 1700 and 1800s. Her first book, Marie Antoinette’s Confidante: The Rise and Fall of the Princesse de Lamballe, discusses the French Revolution and looks at the relationship between Marie Antoinette and the Princesse de Lamballe.

Facebook | Twitter | Google+ | Instagram | Pinterest

That account is chilling. Really makes you appreciate some of today’s advances. Fun fact, anaesthetic and dentistry are widely considered to be the biggest advantages of living now, as opposed to the past. Thanks for posting this.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I could see that! I always think of penicillin, more reliable contraception, and knowing about hand hygiene! I can’t imagine what this must have been like. I hope there was laudanum in that cordial!

LikeLiked by 2 people

Absolutely. It’s a wonder anybody survived surgery at all. The pain alone could have been enough to kill.

LikeLike

Wow, did not know that about Mrs. Burney. How terrible! Her account is so vivid I could almost feel it.

LikeLike

[…] Frances Burney d’Arblay was an English satirical novelist, diarist, and playwright better known as Fanny Burney. In 1811, before anesthesia was invented, she had a mastectomy aided by nothing more than a wine cordial. To learn more about this event, click here. […]

LikeLike

[…] He co-led the surgical team that performed a pre-anesthetic mastectomy on the famous English satirical novelist, diarist and playwright Frances Burney on 30 September 1811. The surgery occurred in Paris and Burney’s detailed account of her operation provides insight into early 19th century doctor-patient relationships and surgical methods performed in a patient’s home. To learn more about this surgery, I did a guest post titled, “Fanny Burney and her Mastectomy” at Jessica Cale’s blog, so click here. […]

LikeLike

She may have lost her breasts but she certainly had balls!

LikeLike

Damn right! 😁

LikeLike

[…] the treatment of cancer. One suspects the following operation was more painful than reported (see Frances Burney’s account of her mastectomy conducted by […]

LikeLike

Brave woman.

LikeLike

[…] tackled the subject included Swift, Richardson, Goldsmith, Aubrey and Defoe. Women writers included Frances Burney and Charlotte Smith. Sarah Fielding’s novel The Governess (1749) was set in a girls’ boarding […]

LikeLike