Meth didn’t come out of nowhere. Like cocaine, heroin, and morphine, it has its origins in 19th century Germany. When Romanian chemist Lazăr Edeleanu first synthesized amphetamine in 1887, he couldn’t have known that his creation would evolve into a substance that would one day help to fuel a world war. Nagai Nagayoshi took it a step closer when he synthesized methamphetamine in 1893. It was transformed into the crystalline form we know today by Japanese pharmacologist Akira Ogata in 1919, at which point it found its way back to Germany, where the conditions were just right for another pharmacological breakthrough.

Drugs and the Weimar Republic

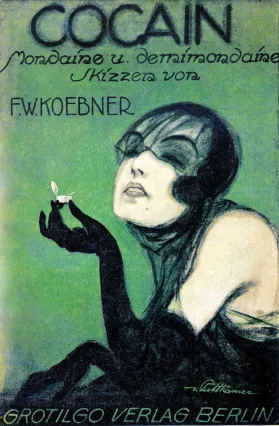

Drugs were not unknown to Berlin. Okay, that’s an understatement. Weimar Berlin was soaked in them. Not only were drugs like morphine, heroin, and cocaine legal, but they could be purchased from every street corner and were all but issued to those attending the legendary nightclubs, where any kink or perversion up to an including BDSM, public orgies, and voyeurism happened on the regular.(1)

Dancer Anita Berber, the It Girl of Weimar Berlin, was known to go about her business wearing nothing but a sable coat and an antique brooch stuffed with cocaine (pictured). She was such an exhibitionist, the local sex workers complained that they couldn’t keep up with the amount of skin she was showing. Of all the idiosyncratic breakfasts of history, Berber’s still stands out: she was said to start every day with a bowl of ether and chloroform she would stir with the petals of a white rose before sucking them dry.

She wasn’t the only one. Having lost its access to natural stimulants like tea and coffee along with its overseas colonies in the Treaty of Versailles, Germany was in need of synthetic assistance. Norman Ohler explains:

“The war had inflicted deep wounds and caused the nation both physical and psychic pain. In the 1920s drugs became more and more important for the despondent population between the Baltic Sea and the Alps. The desire for sedation led to self-education and there soon emerged no shortage of know-how for the production of a remedy.”

Produce they did. Eighty percent of the global cocaine market was controlled by German pharmaceutical companies, and Merck’s was said to be the best in the world. Hamburg was the largest marketplace in Europe for cocaine with thousands of pounds of it passing through its port legally every year. The country of Peru sold its entire annual yield of raw cocaine to German companies. Heroin, opium, and morphine were also produced in staggering quantities, with ninety-eight percent of German heroin being exported to markets abroad.

How were drugs able to flourish to such an extent? For one thing, they were legal. Many veterans of the First World War were habitually prescribed morphine by doctors who were addicted to it themselves. It wasn’t viewed as a harmful drug but as a necessary medical treatment for chronic pain and shell shock. Further, the line between drug use and addiction was uncertain. In spite of countless people regularly indulging in everything from cocaine to heroin for medical as well as recreational purposes, few were considered to be addicts. Drug use was not a crime, and addiction was seen as a curable disease to be tolerated.

As historian Jonathan Lewy explains:

“Addicts stemmed from a higher class in society. Physicians were the most susceptible professional group to drug addiction. Instead of antagonizing this group, the regime tried to include physicians and pharmacists in their program to control drugs. In addition, German authorities agreed that the war produced addiction; in other words, the prized veterans of the First World War were susceptible, and none of the political parties in the Weimar Republic, least of all the National Socialist Party, wished to antagonize this group of men.”

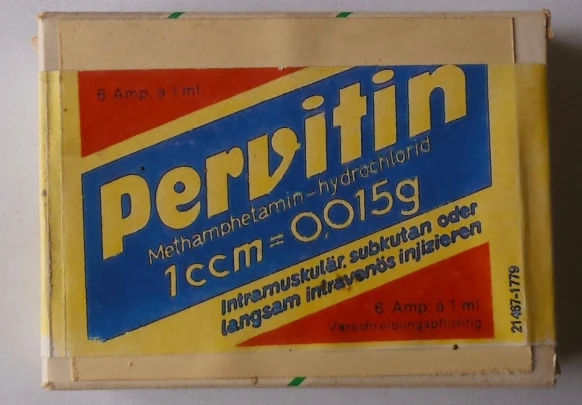

Pervitin, The Miracle Pill

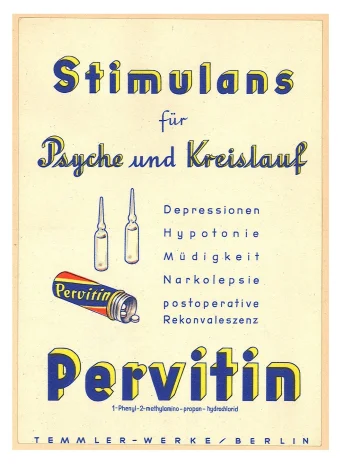

On Halloween 1937, Pervitin was patented by Temmler, a pharmaceutical company based in Berlin. When it hit the market in 1938, Temmler sent three milligrams to every doctor in the city. Many doctors got hooked on it, and, convinced of its efficacy, prescribed it as study aid, an appetite suppressant, and a treatment for depression.

Temmler based its ad campaign on Coca-Cola’s, and the drug quickly became popular across the board. Students used it to help them study, and it was sold to housewives in chocolate with the claim that would help them to finish their chores faster with the added benefit that it would make them lose weight (it did). By 1939, Pervitin was used to treat menopause, depression, seasickness, pains related to childbirth, vertigo, hay fever, schizophrenia, anxiety, and “disturbances of the brain.”

Temmler based its ad campaign on Coca-Cola’s, and the drug quickly became popular across the board. Students used it to help them study, and it was sold to housewives in chocolate with the claim that would help them to finish their chores faster with the added benefit that it would make them lose weight (it did). By 1939, Pervitin was used to treat menopause, depression, seasickness, pains related to childbirth, vertigo, hay fever, schizophrenia, anxiety, and “disturbances of the brain.”

Army physiologist Otto Ranke immediately saw its potential. Testing it on university students in 1939, he found that the drug enabled them to be remarkably focused and productive on very little sleep. Pervitin increased performance and endurance. It dulled pain and produced feelings of euphoria, but unlike morphine and heroin, it kept the user awake. Ranke himself became addicted to it after discovering that the drug allowed him to work up to fifty hours straight without feeling tired.

Despite its popularity, Pervitin became prescription only in 1939, and was further regulated in 1941 under the Reich Opium Law. That didn’t slow down consumption, though. Even after the regulation came in, production increased by an additional 1.5 million pills per year. Prescriptions were easy to come by, and Pervitin became the accepted Volksdroge (People’s Drug) of Nazi Germany, as common as acetaminophen is today.

Although the side effects were serious and concerning, doctors continued to readily prescribe it. Doctors themselves were among the most serious drug abusers in the country at this time. An estimated forty percent of the doctors in Berlin were known to be addicted to morphine.

As medical officer Franz Wertheim wrote in 1940:

“To help pass the time, we doctors experimented on ourselves. We would begin the day by drinking a water glass of cognac and taking two injections of morphine. We found cocaine to be useful at midday, and in the evening we would occasionally take Hyoskin (an alkaloid derived from nightshade) … As a result, we were not always fully in command of our senses.”

Its main user base, however, was the army. In addition to the benefits shown during the test on the university students, Ranke found that Pervitin increased alertness, confidence, concentration, and willingness to take risks, while it dulled awareness of pain, hunger, thirst, and exhaustion. It was the perfect drug for an army that needed to appear superhuman. An estimated one hundred million pills were consumed by the military in the pre-war period alone. Appropriately enough, one of the Nazis’ slogans was, “Germany, awake!”

Germany was awake, alright.

Military Use

After its first major test during the invasion of Poland, Pervitin was distributed to the army in shocking quantities. More than thirty-five million tablets of Pervitin and Isophan(2) were issued to the Wermacht and Luftwaffe between April and July of 1940 alone. They were aware that Pervitin was powerful and advised sparing use for stress and “to maintain sleeplessness” as needed, but as tolerance increased among the troops, more and more was needed to produce the same effects.

Pervitin was a key ingredient to the success of the Blitzkrieg (lightning war). In these short bursts of intense violence, speed was everything. In an interview with The Guardian, Ohler summarized:

“The invasion of France was made possible by the drugs. No drugs, no invasion. When Hitler heard about the plan to invade through Ardennes, he loved it. But the high command said: it’s not possible, at night we have to rest, and they [the allies] will retreat and we will be stuck in the mountains. But then the stimulant decree was released, and that enabled them to stay awake for three days and three nights. Rommel and all those tank commanders were high, and without the tanks, they certainly wouldn’t have won.”

Bomber pilots reported using Pervitin to stay alert throughout the Battle of Britain. Launches were often late at night, so German pilots would not make it to London until after midnight. As one bomber pilot wrote:

“You were over London or some other English city at about one or two in the morning, and of course then you’re tired. So you took one or two Pervitin tablets, and then you were all right again … The commander always has to have his wits about him, so I took Pervitin as a precautionary measure. One wouldn’t abstain from Pervitin because of a little health scare. Who cares when you’re doomed to come down at any moment anyway?”

Pervitin was issued to pilots to combat fatigue, and some of its nicknames—“pilot salt,” “Stuka pills,” “Göring pills”—hinted at its use. One commodore fighting in the Mediterranean described the feeling of using it while flying:

“The engine is running cleanly and calmly. I’m wide awake, my heartbeat thunders in my ears. Why is the sky suddenly so bright, my eyes hurt in the harsh light. I can hardly bear the brilliance; if I shield my eyes with my free hand it’s better. Now the engine is humming evenly and without vibration—far away, very far away. It’s almost like silence up here. Everything becomes immaterial and abstract. Remote, as if I were flying above my plane.”

As powerful as Pervitin was, it wasn’t enough. Still, whatever they needed was given to them. By 1944, Vice-Admiral Hellmuth Heye requested something stronger than would enable troops to fight even longer while boosting their self-esteem. Not long after, Kiel pharmacologist Gerhard Orzechowski answered with a newer, stronger pill called D-IX, the active ingredients of which were three milligrams of Pervitin, five milligrams of cocaine, and five milligrams of Eukodal, a painkiller derived from morphine.

Initially tested on prisoners at the Sachsenhausen concentration camp (the victims were forced to walk until they dropped, regardless of how long it took), D-IX was given to the marines piloting one-man U-boats designed to attack the Thames estuary. It was issued as a kind of chewing gum that was to keep the marines awake and piloting the boats for days at a time before ultimately attacking the British. It did not have the intended effect, however. Trapped under water for days at a time, the marines suffered psychotic episodes and often got lost.

The Hangover

No “miracle pill” is perfect, and anything that can keep people awake for days is going to have side effects. Long-term use of Pervitin could result in addiction, hallucination, dizziness, psychotic phases, suicide, and heart failure. Many soldiers died of cardiac arrest. Recognizing the risks, the Third Reich’s top health official, Leonardo Conti, attempted to limit his forces’ use of the drug but was ultimately unsuccessful.

Temmler Werke continued supplying Pervitin to the armies of both East and West Germany until the 1960s. West Germany’s army, the Bundeswehr, discontinued its use in the 1970s, but East Germany’s National People’s Army used it until 1988. Pervitin was eventually banned in Germany altogether, but methamphetamine was just getting started.

Jessica Cale

Sources

Cooke, Rachel. High Hitler: How Nazi Drug Abuse Steered the Course of History. The Guardian, September 25th, 2016.

Hurst, Fabienne. The German Granddaddy of Crystal Meth. Translated by Ella Ornstein. Spiegel Online, May 30th, 2013.

Lewy, Jonathan. The Drug Policy of the Third Reich. Social History of Alcohol and Drugs, Volume 22, No 2, 2008

Ohler, Norman. Blitzed: Drugs in the Third Reich. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. New York, 2015.

Ulrich, Andreas. The Nazi Death Machine: Hitler’s Drugged Soldiers. Translated by Christopher Sultan. Spiegel Online, May 6th, 2005.

(1) Don’t worry. We’re definitely going to cover that.

(2) Isophan: a drug very similar to Pervitin produced by the Knoll pharmaceutical company

Oh my god… I’m gobsmacked. As a veterinarian with a pretty good hold on pharmacology, I’m stunned. Awesome wrapup, Jessica. Well done.

xx

Lizzi Tremayne, Author

LikeLike

Thank you so much, Lizzi! I really appreciate that! 😀

LikeLike

Great post, Jessica. Some things never change. Or we never learn. The parallels to modern society are scary.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks very much! I was really struck by the parallels as well. Particularly the advertising campaigns — drugs are still advertised this way and samples are given to doctors, but no one thinks anything of it because they’re medications. Pervitin was a medication once, too. I wonder how many others are going to turn out to be as dangerous!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Wow! That’s fascinating.

LikeLike

Thanks, Jude! Ohler’s book is a great read. It’s a huge subject!

LikeLike

Excellent blog today. I’m always learning something new. And some things never change.

LikeLike

Thanks, Cynthia! You’re absolutely right. The more things change, the more they stay the same…

LikeLike

I’m impressed, I have to admit. Rarely do I encounter a blog that’s both educative and interesting, and without a doubt, you have hit the nail on the head. The issue is an issue that not enough people are speaking intelligently about. I’m very happy I stumbled across this in my hunt for something relating to this.

LikeLike

[…] https://dirtysexyhistory.com/2018/04/26/pervitin-the-peoples-drug-how-methamphetamine-fueled-the-thi… […]

LikeLike