Picture the ideal nineteenth century English beauty: pale, almost translucent skin, rosy cheeks, crimson lips, white teeth, and sparkling eyes. She’s waspishly thin with elegant collarbones. Perhaps she’s prone to fainting.

Picture the ideal nineteenth century English beauty: pale, almost translucent skin, rosy cheeks, crimson lips, white teeth, and sparkling eyes. She’s waspishly thin with elegant collarbones. Perhaps she’s prone to fainting.

It shouldn’t be difficult to imagine; numerous depictions survive to this day, and the image is still held up as the gold standard for Caucasian women. At this point, it’s so embedded in the Western psyche as beauty that it doesn’t occur to us to question it. Of course that’s beautiful. Why wouldn’t it be?

By the nineteenth century, beauty standards in Britain had come a long way from the plucked hairlines of the late Middle Ages and the heavy ceruse of the Stuart period. Fashionable women wanted slimmer figures because physical fragility had become associated with intelligence and refinement. Flushed cheeks, bright eyes, and red lips had always been popular, particularly among sex workers (they suggested arousal), and women had been using cosmetics like belladonna, carmine, and Spanish leather for years to produce those effects when they didn’t occur organically.

Bright eyes, flushed cheeks, and red lips were also signs of tuberculosis.

Tuberculosis—known at the time as consumption, phthisis, hectic fever, and graveyard cough—was an epidemic that affected all classes and genders without prejudice. Today, an estimated 1.9 billion people are infected with it, and it causes about two million deaths each year. At the time, it was mainly associated with respectable women (although there are no few depictions of sex workers dying of it*) and thought to be triggered by mental exertion or too much dancing.** Attractive women were viewed as more susceptible to it because tuberculosis enhanced their best features. It was noted to cause pale skin, silky hair, weight loss, and a feverish tinge to the face (along with less desirable symptoms including weakness, coughing up blood, GI upset, and organ failure), and it was treated with little to no effect with bleeding, diet, red wine, and opium.

Although having an active (rather than latent) case of consumption was all but a death sentence, it didn’t inspire the revulsion of other less attractive diseases until the end of the 19th century when its causes were better understood.

In 1833, The London Medical and Surgical Journal described it in almost affectionate terms: “Consumption, neither effacing the lines of personal beauty, nor damaging the intellectual functions, tends to exalt the moral habits, and develop the amiable qualities of the patient.”

Of course it didn’t only affect women. The notion that it was caused by mental exertion—along with the high number of artists and intellectuals who lost their lives to it—also led to its association with poets. John Keats died of it at 26. His friend Percy Shelley—also infected—wrote tributes to Keats that attempted to explain consumption not as a disease, but as death by passion. Bizarrely, a symptom that is unique to consumption is spes phthisica, a euphoric state that can result in intense bursts of creativity.*** Keats’ prolific final year of life has been attributed to his consumption, and spes phthisica was viewed by some as necessary for artistic genius.

As Alexandre Dumas (fils) wrote in 1852: “It was the fashion to suffer from the lungs; everybody was consumptive, poets especially; it was good form to spit blood after any emotion that was at all sensational, and to die before reaching the age of thirty.”

Because of its association with young women and poets, the disease itself came to represent beauty, romantic passion, and hyper sexuality. As far as illnesses went, it was considered to be rather glamorous, and in a culture half in love with death, it inspired its fair share of tributes. There are numerous romantic depictions of young women wasting away in death beds at the height of their beauty. Women with consumption were regularly praised for the ethereal loveliness that came from being exceptionally thin and nearly transparent.

Picture that ideal nineteenth century beauty again: that complexion is almost a pallor, and you can see her veins through it. Those lips, eyes, and cheeks are all indicative of a constant low-grade fever. Her teeth are so white they’re almost as translucent as her skin. And her figure? She’s emaciated due to the illness and the chronic diarrhea that comes with it. If she faints, it’s more to do with the lack of oxygen in her blood than the tension of her corset. The sicker she gets, the more beautiful she becomes, until she’s gone; the beauty is all the more poignant because of its impermanence. This beauty can’t last, and it’s as deadly as it is contagious.

Only a fool would wish for it, so what’s a healthy girl to do?

If you didn’t have consumption but wanted the look, there were two things you could do: wait (at its peak between 1780 and 1850, it is estimated to have caused a quarter of all deaths in Europe. Statistically, you would have had a fair chance of getting it), or fake it. Corsets could be made to narrow the waist and encourage a stooped posture, and necklines were designed to show off prominent collar bones. As for the rest, people could try:

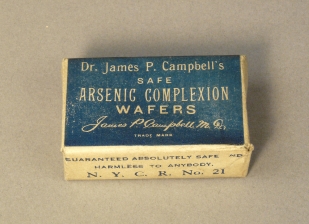

Arsenic Complexion Wafers

Although arsenic was known to be toxic, it was used throughout the nineteenth century in everything from dye to medication. Eating small amounts of arsenic regularly was said to produce a clear, ghostly pale complexion. Lola Montez reported that some women in Bohemia frequently drank the water from arsenic springs to whiten their skin.

Stop Eating

In The Ugly-Girl Papers, S.D. Powers offers her own advice for achieving consumptive skin: “The fairest skins belong to people in the earliest stages of consumption, or those of a scrofulous nature. This miraculous clearness and brilliance is due to the constant purgation which wastes the consumptive, or to the issue which relieves the system of impurities by one outlet. We must secure purity of the blood by less exhaustive methods. The diet should be regulated according to the habit of the person. If stout, she should eat as little as will satisfy her appetite.”

How little? Writing in the third person, she uses herself as an example: “Breakfast was usually a small saucer of strawberries and one Graham cracker, and was not infrequently dispensed with altogether. Lunch was half an orange—for the burden of eating the other half was not to be thought of; and at six o’clock a handful of cherries formed a plentiful dinner. Once a week she did crave something like beef-steak of soup, and took it.”

Olive-Tar

For “fair and innocent” skin that mimics the effects of consumption, The Ugly-Girl Papers offers the following recipe: “Mix one spoonful of the best tar in a pint of pure olive oil or almond oil, by heating the two together in a tin cup set in boiling water. Stir till completely mixed and smooth, putting in more oil if the compound is too thick to run easily. Rub this on the face when going to bed, and lay patches of soft old cloth on the cheeks and forehead to keep the tar from rubbing off. The bed linen must be protected by old sheets folded and thrown over the pillows. The odor, when mixed with oil, is not strong enough to be unpleasant—some people fancy its suggestion of aromatic pine breath—and the black, unpleasant mask washes off easily with warm water and soap. The skin comes out, after several applications, soft, moist, and tinted like a baby’s. The French have long used turpentine to efface the marks of age, but olive-tar is pleasanter.”

White Lead

Lead had been used as the primary ingredient for ceruse and other forms of foundation and powder for centuries. It was known to cause skin problems over time (and, you know, lead poisoning). In the nineteenth century, it was still used for the same purpose and appeared in paints and skin enamels in Europe and the United States.

Lavender Powder

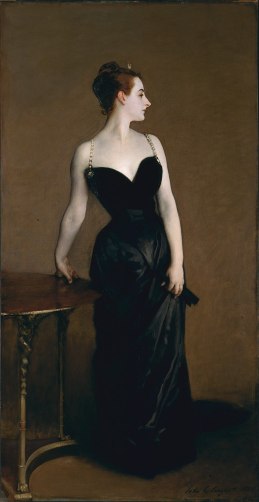

If the pallor of consumption didn’t occur naturally or with the aid of arsenic, it could be imitated with the use of lavender colored powder. Usually applied over ceruse or other foundation made from white lead, it gave the skin a bluish, porcelain shade. Perhaps the best known example of this is John Singer Sargent’s Madame X. The model, Virginie Gautreau, was known to use lavender powder to create her dramatically pale complexion. She was said to be a master of drawing fake veins on with indigo, and she painted her ears with rouge to add to the illusion of translucence.

Rouge

Commonly sold and sometimes made at home, rouge was everywhere. Made from toxic bismuth or vermilion, or carmine from cochineal beetles, it was applied to cheeks, lips, ears, and sometimes even nostrils to make them appear transparent. It came in liquid, cream, and powder forms, and Napoleon’s Empress Josephine is said to have spent a fortune on it. The Ugly-Girl Papers offers this recipe for Milk of Roses, which sounds rather nice:

“(Mix) four ounces of oil of almonds, forty drops of oil of tarter, and half a pint of rose-water with carmine to the proper shade. This is very soothing to the skin. Different tinges may be given to the rouge by adding a few flakes of indigo for the deep black-rose crimson, or mixing a little pale yellow with less carmine for the soft Greuze tints.”

Ammonia

The Ugly-Girl Papers recommends ammonia for use as both a hair rinse and, worryingly, a depilatory. For healthy hair, Powers recommends scrubbing it nightly with a brush in a basin of water with three tablespoons of ammonia added. Hair should then be combed and left to air dry without a night cap.

Lemon Juice and Eyeliner

To achieve the ideal feverish “sparkling eyes,” some women still used belladonna (which could cause blindness) while others resorted to putting lemon juice or other irritants in their eyes to make them water. Eyes, eyelashes, and eyebrows could also be defined. Powers advises: “All preparations for darkening the eyebrows, eyelashes, etc., must be put on with a small hair-pencil. The “dirty-finger” effect is not good. A fine line of black round the rim of the eyelid, when properly done, should not be detected, and its effect in softening and enlarging the eyes is well known by all amateur players.”

Jessica Cale

Sources

Day, Carolyn. Consumptive Chic: A History of Beauty, Fashion, and Disease. (2017)

Dumas, Alexandre (fils). La Dame Aux Camélias. (1852)

Klebs, Arnold. Tuberculosis: A Treatise by American Authors on its Etiology, Pathology, Frequency, Semeiology, Diagnosis, Prognosis, Prevention, and Treatment. (1909)

Meier, Allison. How Tuberculosis Symptoms Became Ideals of Beauty in the 19th Century. Hyperallergic. January 2nd, 2018.

Montez, Lola. The Arts of Beauty: or Secrets of a Lady’s Toilet. (1858)

Morens, David M. At the Deathbed of Consumptive Art. Emerging Infectious Diseases, Volume 8, Number 11. November 2002.

Mullin, Emily. How Tuberculosis Shaped Victorian Fashion. Smithsonian.com, May 10th, 2016.

Pointer, Sally. The Artifice of Beauty: A History and Practical Guide to Perfumes and Cosmetics. (2005)

Powers, S. D. The Ugly-Girl Papers, or Hints for the Toilet. (1874)

Zarrelli, Natalie. The Poisonous Beauty Advice Columns of Victorian England. Atlas Obscura, December 17th, 2015.

Notes

*Depictions of sex workers dying of tuberculosis: La Traviata, Les Misérables, La Bohème, and now Moulin Rouge, etc. In the 19th century, consumption was portrayed as a kind of romantic redemption for sex workers through the physical sacrifice of the body.

**Although dancing itself wouldn’t have done it, the disease was so contagious that it could be contracted anywhere people would be at close quarters—dancing at balls with multiple partners could have reasonably been high-risk behavior.

***You know what else does that? Tertiary syphilis. How do you know which one you have? If you’re coughing blood, it’s consumption. If your skin is falling off, it’s syphilis. Either way, you’re going to want to call a doctor.

Fascinating, thank you!

TB was also called the ‘White Death’, and less glamorously as ‘The Captain of all these Men of Death’.

LikeLike

Reblogged this on Laura Libricz, Authoress.

LikeLike

Fascinating post! Thanks for sharing 🙂

LikeLike

Quite an interesting topic. Thank you for all the information of what someone would use to feign consumption. Fascinating.

LikeLike

Wow! This is fascinating. How could spitting or coughing up blood even be considered a good thing? It defies imagination what people did…arsenic, lead, tb.

LikeLike

Right? I think they overlooked that part (also the death part). It’s so crazy to me that they knew arsenic was poisonous but still thought using it in small quantities was okay. There are still a few things like that today — I wonder what people will think we were crazy to use when they look back on us in a hundred years!

LikeLike

It seems unbelievable, but I saw a very sick, anorexic girl this year, who clearly recognised that her organs were closing down. Yet she still wanted to lose more weight because of the pleasure that weight loss would bring.

LikeLike

Fantastic history! It makes me wonder what unhealthy things we are doing and promoting now for the sake of beauty… Thank you for sharing!

LikeLike

[…] objectified and the description of the beauty changes through time. In the nineteenth century, the ideal English beauty was described as having translucent skin, rosy cheeks and so slim that she was prone […]

LikeLike