In the wake of the fourteenth-century plague, which killed over half of Italy’s populations, cities were faced with a crisis. To make matters worse, Italian men seemed uninterested in repopulating the peninsula, struck by a sin worse than death—same-sex attraction. Fifteenth-century preacher Bernardino of Siena railed that “even the Devil flees in horror at the sight of this sin.”

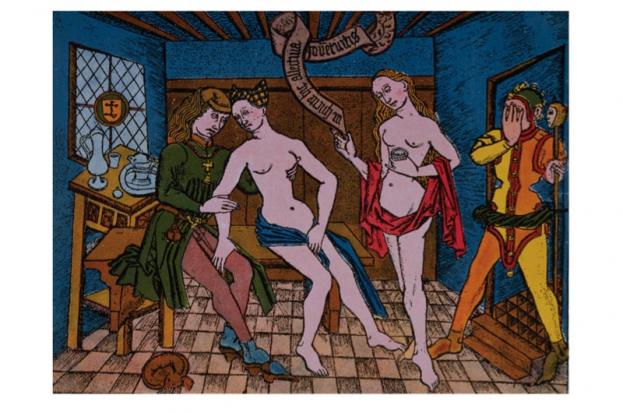

Italian cities responded by encouraging prostitution. In 1403, the government of Florence opened an office to promote prostitution in order to prevent the worse sin of sodomy. Venice legalized prostitution in 1358 and created a brothel district in the commercial heart of the city, the Rialto.

Prostitution was a reality of life in Renaissance Italy. But in spite of its legality, Renaissance Italians had a mixed opinion of the profession. The medieval church had declared prostitution a “necessary evil,” drawing on St. Augustine of Hippo’s proclamation that “If you do away with whores, the world will be consumed with lust.” Thomas Aquinas likewise declared in the thirteenth century that “If prostitution were to be suppressed, careless lusts would overthrow society.” Aquinas likened prostitution to a sewer in a palace—if you took it away, the building would overflow with pollution. Or, more specifically, “Take away prostitutes from the world and you will fill it with sodomy.”

Prostitutes, then, served as receptacles of sin, protecting the rest of society from male lust. And, in particular, they kept male passions focused on women, rather than other men.

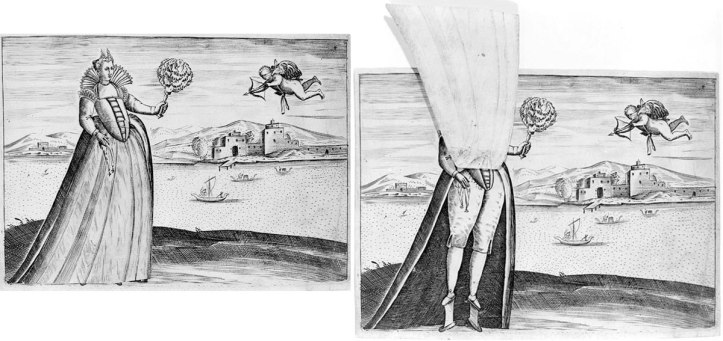

But legalization did not mean prostitution was an esteemed profession. It was heavily regulated, as cities passed laws to ensure that honorable citizens could avoid the corrupting influence of prostitutes. Venetian prostitutes had to wear a yellow scarf in public. In 1384, Florence passed a law forcing prostitutes to wear bells on their heads, gloves, and high-heeled shoes.

Let’s talk for a minute about these special shoes—they were called chopines, and they likely originated with Venetian prostitutes. These heels could be up to twenty-four inches high (and I thought four inch heels were tricky!). Patrician women were so enamored with the style that laws forcing prostitutes to wear the shoes were passed to discourage “good” women from donning them. Those efforts failed.

Renaissance prostitution was meant to channel male lust in appropriate directions, and as such, prostitution reinforced gender norms. Venice, for example, encouraged women to run brothels, because men relying on the earnings of prostitutes inverted normal gender relations. The city worried that men who lived off of women’s earnings would become dangerously lazy and fall into a life of crime. In an ironic twist, this attitude put a great deal of power in the hands of “matrons,” who were integrated into Venetian business at multiple levels.

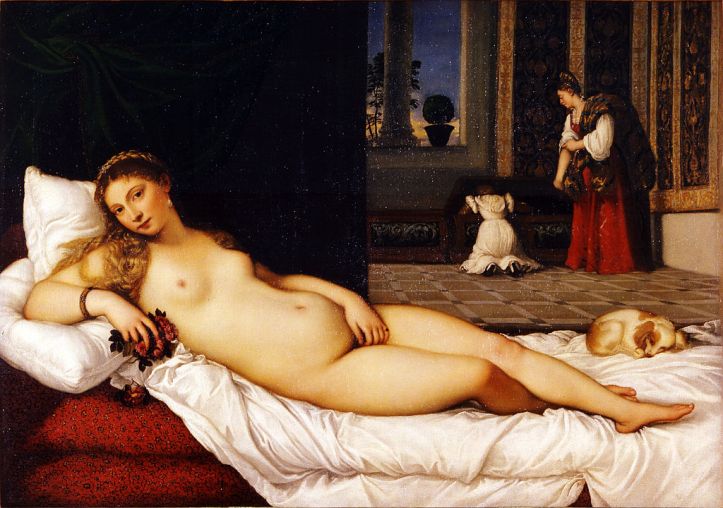

Expensive, educated courtesans were also able to use their position to enhance their independence. Tullia d’Aragona, a sixteenth-century Roman courtesan, published multiple books and owned many houses. Another famous courtesan, Veronica Franco of Venice, was a published poet of great distinction. When King Henry III of France visited Venice in 1574, the city hired Franco to entertain him. These two women were widely admired for their works, and had a degree of freedom unmatched by their married cousins. Another courtesan, Angela del Moro, served as the model for Titian’s Venus of Urbino.

Legalized prostitution reinforced gender norms, but in limited cases it provided opportunities for women to assert power. As madams or courtesans, women could own property, publish, and achieve social acclaim. Yet for the majority of Renaissance Italian prostitutes, it was a hard life, and often not one they chose. Prostitutes were exploited by the brothels and by the cities, often treated no better than the sewers to which Aquinas likened them. They existed on the margins, their exploitation justified for the “greater good” of society.

Sylvia Prince is a history professor and author. Her debut novel, The Lion and the Fox, is set in the cutthroat world of Renaissance Florence, and follows Niccolo Machiavelli as he solves the murder of a Medici. It also features male and female prostitutes, as well as a female brothel owner. Find out more at Sylvia’s website www.sylviaprincebooks.com and find her on Facebook and Twitter @sprincebooks.

Sources

Brackett, John K. “The Florentine Onesta and the Control of Prostitution, 1403-1680.” Sixteenth Century Journal, v. 24, no. 2 (Summer 1993), pp. 273-300.

Clarke, Paula C. “The Business of Prostitution in Early Renaissance Venice.” Renaissance Quarterly, v. 68 no. 2 (Summer 2015), pp. 419-464.

Mormondo, Franco. The Preacher’s Demons: Bernardino of Siena and the Social Underworld of Early Renaissance Italy

Reblogged this on Emma Rose Millar and commented:

Great post on prostitution and same sex attraction from Dirty Sexy History.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks, Emma! ❤

LikeLike

That’s a powerful essay. Thanks for publishing it.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I really enjoyed this one, too. Thanks for stopping by! 🙂

LikeLike

The more things change, the more they stay the same.

LikeLiked by 1 person

True! I was thinking that looking at those chopines — they remind me of those enormous fetish platforms you see sometimes. I have a friend who calls them “pole-dancing shoes.” LOL

LikeLike

Great Post!

LikeLiked by 1 person

I’m a fan and avid researcher of Italian history, and I must say this is new information. I found it highly interesting. Thank you.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Really interesting information here. Thanks for writing and sharing.

LikeLiked by 1 person

[…] para mantener a raya a todos los jóvenes ebrios fuera de peligro. San Agustín de Hipona dijo una vez que “si eliminas a las putas, el mundo se verá consumido por la lujuria”. Del mismo […]

LikeLike

[…] example, courtesans were quite respectable. In Renaissance Italy, though, ladies of the night had to wear bells. Around the same time, in Tokugawa Japan, people argued that geisha made better companions than […]

LikeLike