On August 24, 79AD, the day after Vulcanalia, the festival of the god of fire, Hell came to the Gulf of Naples. Vesuvius erupted and a searing pyroclastic cloud scorched, choked, and buried the prosperous provincial Roman cities of Pompeii and Herculaneum under thousands of tons of blistering ash and boiling mud. The thermal energy released dwarfed that of the atomic bombings of Japan, and to the witnesses and victims it must have felt like the apocalypse. ‘You could hear the shrieks of women, the wailing of infants, and the shouting of men,’ wrote Pliny the Younger, ‘People bewailed their own fate or that of their relatives, and there were some who prayed for death in their terror of dying. Many besought the aid of the gods, but still more imagined there were no gods left, and that the universe was plunged into eternal darkness for evermore’ (Hutchinson: 1931, 495).

Entombed and oddly preserved at the moment of their destruction, the ruins lay undisturbed for over 1,600 years, while above them the Roman Empire fell, the Ostrogoths, Byzantines, and Lombards fought for control of the region, the early-Christian Church became established, the Kingdom of Sicily rose, the Black Death decimated Europe, the Reformation came, and Florence, Milan, and Venice became the cultural hubs of the Renaissance. Then one day in 1709, a peasant in the small town of Resina came across some interestingly coloured marble and alabaster while digging a well…

Initial excavations in search of more of the valuable gallo antico yellow marble during the Austrian occupation of Southern Italy were inconclusive and abandoned after a couple of years. Almost thirty years later, when the region was once more under Spanish control, the army engineer Roque Joaquín de Alcubierre was overseeing the building of a new summer palace for King Charles of the Two Sicilies when he discovered – or more correctly rediscovered – the remains of Herculaneum. With permission and a modest grant from Charles of Bourbon, who saw the potential for the discovery and display of Roman artefacts as a symbol of the continuing cultural significance of Naples, Alcubierre began the first serious excavation of the site. His workmen soon unearthed the amphitheatre of Herculaneum, and over the next eight years provided a steady stream of remarkably well-preserved artefacts for the new Museo Borbonico in Naples.

By 1745, however, the stream had begun to run dry. Archaeologists and engineers therefore turned their attention to ‘Cività Hill,’ a few miles south-east of the Herculaneum dig. ‘Cività’ means ‘City,’ and under the hill, where local legend suggested a lost city lie, possibly the small seaside town of Stabiae (also obliterated by Vesuvius), Alcubierre found the much larger port of Pompeii. The going was much easier as the city had been buried by ash rather than the mud that had set like concrete over Herculaneum, and the first intact fresco was found in 1748, in what appeared to be a dining room in a house that also contained a skeleton clasping Julio-Claudian and Flavian coins, with all that implies for the unfortunate occupant’s priorities during the cataclysm.

Classical Graeco-Roman culture had always been the foundation of art and learning in Europe, a model for ‘Civilization,’ with obvious parallels in particular drawn between the might of the Roman Empire in the past and the British in the present, the global superpower that would dominate the 19th century. Never had the modern world had such a direct window to the ancient as the one afforded by these excavations, but despite what scholars thought they knew about the glory of Rome, they were not at all ready for what they found in the ashes. There were sculptures, ceramics and frescoes depicting Roman deities, natural, mythical and historical scenes, and celebrating sporting prowess; there was even political graffiti carved into walls, and plenty of those clean, white marble statues so beloved by classicists, symbolising purity of body and spirit through aesthetic perfection. So far, so good; nothing Thomas Babington Macaulay wouldn’t have included in his epic poem ‘Pompeii’ or the Lays of Ancient Rome. But there was also something else, and a lot of it; and by 1758 rumours began to circulate in antiquarian circles concerning apparently ‘lascivious’ frescoes being discovered beneath the ruins.

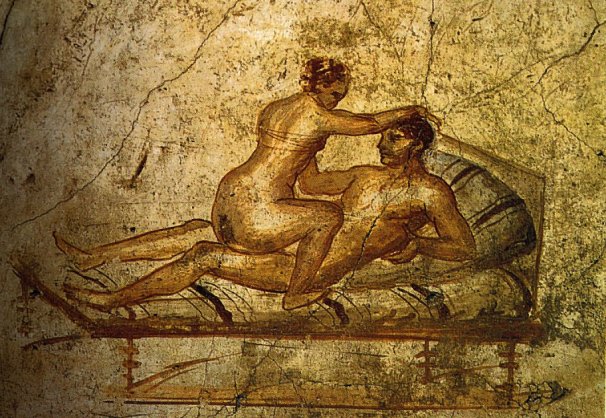

Up until the cities of Vesuvius were excavated, Roman artefacts existed as cultural diaspora, the result often of quite random finds, and subject to millennia of subtle Christian censorship and academic classification. This meant in practice that those clean marble statues became the mark of antiquity, while anything more raunchy or challenging was lost among the acceptable works of art, or possibly even quietly destroyed. But Herculaneum and, especially, Pompeii afforded a different opportunity for historical study. By being effectively frozen in time, the descendants of Rome finally saw how their ancestors really lived, and they lived in a world surrounded by dirty pictures.

Explicit sexual imagery was everywhere, in public and private spaces, and across social classes; clearly, anyone could unproblematically own and view this material. Unsurprisingly, there were ‘lascivious’ pieces in brothels; but there were also paintings depicting couples making love in a variety of positions in the homes of artisans, merchants and politicians, in the quarters of their servants and their slaves, as well as the public baths, while erect phalluses were carved into paving stones and doorways as symbols of potent protection (right), and beautifully rendered statues of deities cavorting with both animals and human beings were proud centrepieces of any fashionable piazza. Discovered in its original context, whether an individual piece was intended to titillate, amuse, or ward off the evil eye, it was apparent that this was not untypical, and that erotic art must have been common throughout the empire and an everyday part of Roman life.

A particularly impressive and representative example was unearthed at the Villa dei Papiri, a country house about halfway up the slope of the volcano, believed to have been built by Lucius Calpurnius Piso Caesoninus, the father-in-law of Julius Caesar. The villa is named for its library, which contained nearly 2000 papyrus scrolls, charred but preserved, making it the most complete and intact classical library ever discovered. The villa was also notable for its owner’s large collection of statuary, which included an intact and intricately carved marble, about six inches tall, of the god Pan on his knees penetrating a she-goat (below). ‘It is impossible not to admire the expression of sensuous passion and intense enjoyment depicted on the Satyr’s features,’ wrote the French antiquarian Cesar Famin in his privately published catalogue Musee royal de Naples; peintures, bronzes et statyues Erotiques du cabinet secret, avec leur explication (1816), adding, ‘and even on the countenance of the strange object of his passion.’ He goes on to cite Herodotus, Virgil and Plutarch to demonstrate that ‘The crime of bestiality was not rare among the ancients’ (Fanin: 1871, 22).

And the shocking revelations did not stop there. Diggers also found ornate drinking bowl masks fashioned like mouths but with a penis instead of a tongue, several bronze tintinnabulums – a kind of hanging chime depicting a winged phallus with little bells attached to it (below right) – a terracotta lamp in the shape of a particularly well-endowed faun, icons of Priapus, fertility god, protector of livestock, fruit, gardens and male genitalia, usually depicted with a large and permanent erection (hence the term ‘priapism’), and a two-foot tall painted phallus on a limestone plinth in the garden. The Catholic archaeologists were nonplussed. In their culture, sex was the ultimate taboo, with the phallus and representations thereof completely hidden from view, let alone graven images doing it in public. Their instinct was to hide it up. King Charles himself therefore placed the statue of Pan and the goat under the supervision of the royal sculptor, Joseph Canart, with strict injunction that no one should be allowed to see it.

As the art historian Walter Kendrick has argued, similar artefacts found elsewhere over the centuries had very probably ‘succumbed to the zealous progress of Christianity’ (Kendrick, 1996: 10); but the sheer volume of explicit material unearthed around Vesuvius presented excavators with a problem not so easily disposed of, although some Pompeii frescoes were subsequently vandalised by outraged diggers. (We know this because contemporary records include sketches of paintings that survived the volcano but have since been obliterated.) Experts and politicians knew that these artefacts were of priceless archaeological and cultural value, and, in any event, the word was out about their collective existence. They could not be destroyed, but neither could they be publicly exhibited.

The solution was concealment. Like Pan and the goat, the erotic artefacts of Pompeii and Herculaneum were hidden. At the suggestion of Francesco Gennaro Giuseppe, Duke of Calabria and later Francis I, King of the Two Sicilies, over a hundred pieces were locked away in a special room in the Museo Borbonico known as the ‘Gabinetto degli Oggetti Osceni’ or ‘Cabinet of Obscene Objects.’ Access to these objects was limited to ‘persons of mature age and of proven morality’ (qtd in Tang: 1999, 29), which basically meant male scholars of notable social rank, who were deemed to be capable of rising above the baser instincts that exposure to these artefacts might provoke. A royal permit was required, and obviously women, children and members of the lower orders need not apply. What had begun as an Enlightenment project – the excavation of the ruins – had now become, in effect, proto-Victorian, and other ‘secret museums’ were established in Florence, Dresden and Madrid housing ‘obscene relics’ from not only Rome but also Egypt and Greece.

Thus was 19th century European culture reconciled with this erotic challenge from classical antiquity, a final invasion by the Imperium Rōmānum, unleashed from beyond the ashen grave of Vesuvius. And they needed this reconciliation, as Europe had fashioned itself in the Greco-Roman image. That this image was now demonstrably tarnished was potentially catastrophic to the collective sense of civilized identity. As historians such as Simon Goldhill, Lynda Nead and Walter Kendrick have persuasively argued, 19th century archaeologists and classicists overcame their dilemma by creating a new physical and cultural space, where both knowledge and morality were preserved, inventing the category of the ‘obscene object’ and then segregating it, with access both restricted and carefully monitored.

This was, in effect, a political act: the contents of the secret museums were part of classical culture, but not the part that we had inherited, and represented the dark decadence that had destroyed Rome and which the modern world must resist. Art, therefore, should only stimulate aesthetically and intellectually, never physically.

Nead, in fact, has made a strong case for the origin of the word ‘obscene’ as we understand it in the Latin term ob scena, which refers to the space off to the side of a stage (Tang: 1999, 29). While the presence of the material was not denied, museum authorities would act as if it did not exist, in exactly the same way that sex was central to the human condition yet never acknowledged in polite society. A new word was found to describe this material: pornography, from the Ancient Greek πορνογράφος (pornográphos), which in turn was derived from πορνεία (porneía, ‘fornication, prostitution’) and γράφω (gráphō, ‘I depict’).

In 1865, the British Museum established its own Museum Secretum in order to house the erotic components of the private art collection of the antiquarian George Witt, whose bequest contained what amounted to an ‘all or nothing’ clause. Much of this material has now found its way into the main collections, but some of it is still kept under lock and key. My wife and I visited the Witt collection a few years back, while she was researching a paper, and there we saw, its access still restricted to scholars by prior appointment, a terracotta replica of the statue of Pan and the goat.

Works Cited

Fanin, Colonel. (1871). The Secret Erotic Paintings: Pictures and Descriptions of Classical Erotic Paintings, Bronzes and Statues. London.

Hutchinson, W.M.L. (ed). (1931). Letters of Pliny By Gaius Plinius Caecilius Secundus. William Melmoth, (trans). London: William Heinemann.

Kendrick, Walter. (1996). The Secret Museum: Pornography in Modern Culture. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Tang, Isabel. (1999). Pornography: The Secret History of Civilisation. London: Channel 4 Books.

Suggested Further Reading

Carver, Rachael. (2011). Pompeii, Pornography and Power. Norwich: University of the Arts.

Clarke, John R. (2007) Roman Life: 100 B.C. to A.D. 200. New York: Abrams.

— (2007) Looking at Laughter: Humour, Power, and Transgression in Roman Visual Culture, 100 B.C. – A.D. 250. Berkeley: University of California.

— (2006) Art in the lives of ordinary Romans: Visual Representation and Non-elite Viewers in Italy, 100 B.C.-A.D. 315. Berkeley: University of California.

— (2003) Roman Sex: 100 B.C. to A.D. 250. New York: Abrams.

— (2001) Looking at Lovemaking: Constructions of Sexuality in Roman Art, 100 B.C. – A.D. 250. Berkeley: University of California.

Gaimster, David. (2000). ‘Sex and Sensibility at the British Museum.’ History Today L (9), September.

Goldhill, Simon. (2011). Victorian Culture and Classical Antiquity. Princeton: University Press.

Grant, Michael. (1997). Eros in Pompeii: The Erotic Art Collection of the Museum of Naples. New York: Stewart, Tabori & Chang.

— (1979). The Art and Life if Pompeii and Herculaneum. New York, Newsweek.

— (1971). Cities of Vesuvius: Pompeii and Herculaneum. London: Book Club Associates.

Hunt, Lynn. (1993). The Invention of Pornography: Obscenity and the Origins of Modernity, 1500-1800. New York: Zone Books.

Nead, Lynda. (1992). The Female Nude: Art, Obscenity and Sexuality. London: Routledge.

Richun, Amy. ed. (1992). Pornography and Representation in Greece and Rome. Oxford: University Press.

Dr Stephen Carver is a cultural historian, editor and novelist. For sixteen years, he taught literature and creative writing at the University of East Anglia, spending three years in Japan as Professor of English at the University of Fukui. He is presently Head of Online Courses at the Unthank School of Writing. Stephen has published extensively on 19th century literature and history; he is the biographer of the Victorian novelist William Harrison Ainsworth and the author of Shark Alley: The Memoirs of a Penny-a-Liner, a historical novel about the wreck of the troopship Birkenhead. He is currently working on a history of the 19th century underworld for Pen & Sword, and a sequel to Shark Alley.

For more from Dr Carver, visit:

Shark Alley – ‘Re-imagining the Victorian Serial’

Author Blog: Confessions of a Creative Writing Teacher

Academic Blog: Essays on 19th Literature & The Gothic

Long, long ago when I was in secondary school, our divinity teacher was an ordained minister in the Church of Ireland (though he didn’t use his title when teaching). He told us that he had been to Pompeii; he didn’t describe what the frescoes had shown, but said that they were ‘dirty’ and ‘disgusting’. This only served to pique our interest.

LikeLiked by 2 people

[…] To continue reading please click here […]

LikeLike

This definitely intrigued me when I took a Greek and Roman art and architecture history course in college. Still one of the place I want to visit.

LikeLiked by 1 person