On January 31, 1599, John Chamberlain wrote a letter to his friend and relative Dudley Carleton. There, sandwiched between the Duke of Florence complaining of English piracy and poor Sir Henry Poore’s non-life-threatening shot in the head, were the following words: “Here is a great and curious present going to the Great Turke, which no doubt will be much talked of, and be very scandalous among other nations, especially the Germans.”

This “great and curious present” departed England on The Hector in February of 1599, bound for the court of the Ottoman Sultan, Mehmed III. It went as a rather overdue acknowledgment of his becoming Sultan upon the death of his father in 1595, and it was to be presented by the English representative, Henry Lello, so that he could kiss the hand of the Sultan and be recognized as England’s ambassador. The gift was a magnificent clockwork organ, sadly smashed just a few short years later, and its maker, who travelled with it on The Hector, was Thomas Dallam.

Dallam is a fascinating figure. He was no sailor, soldier, diplomat, or spy; he seems never to have even left England before. But from February 1599 to April 1600, he’d journey to and from the city he mostly called Constantinople (and once or twice Stamboul), and he’d write all about it. He’d write about encounters with Dunkirker pirates shortly after departure, his annoyance at the captain’s behaviour, “an infinite body of porpoises,” and the behaviour of Turks. He runs for his life on a few occasions, notes as the ship passes the birthplace of Pythagoras or of Saul, and eventually gives an incredibly stressful solo performance for the Sultan and 400 of his attendants.

One of the aspects that is most interesting about this unlikely Elizabethan diplomat and world traveller, is how strikingly he sometimes resembles the modern tourist. He grumbles at the greed of foreign officials. He wonders at the climate off the shores of southern Spain, struck by the difference from England in much the same way that many, many, more English travellers would be in centuries to come. Most amusingly, he hammers off for himself a little piece of the walls of Troy, an apparently timeless inclination to possess a bit of history.

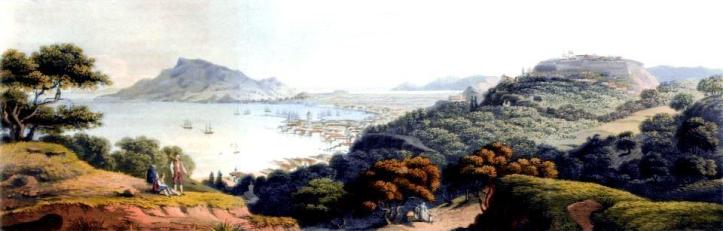

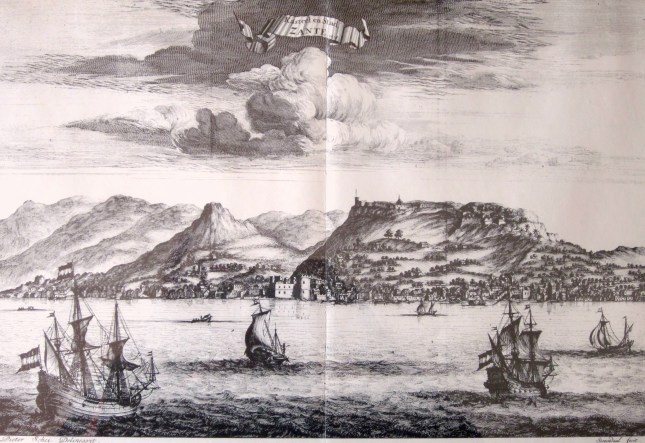

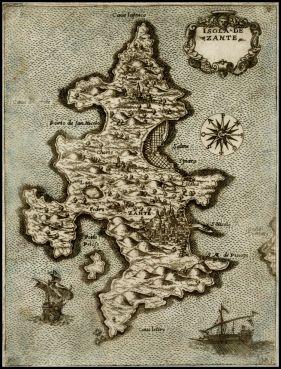

For all of Dallam’s adventures, and his generally naive role in some rather important diplomatic dealings, one of the episodes that he gives the most attention to in his writing is an adventure of a different kind: an unsuccessful attempt to pay for sex in a hilltop house, on a Greek island he identifies as Zante, in the month of April, 1599. Zante, now known as Zakynthos, was a possession of the Most Serene Republic of Venice, but our narrator tells us that tribute was paid for it, yearly or quarterly, to “the great Turk,” the Ottoman Sultan.

Dallam and the other men of The Hector had sat at anchor for 6 long, dull days. Having most recently left Algiers, and with Turkish goods and men aboard, they were waiting out the quarantine required of a ship arriving from any part of the Ottoman domain without a Venetian letter of health. These days, tantalizingly close to shore but denied access to its pleasures, gave Dallam time to admire a little mountain. It was close to the sea, he wrote, very green, and promised to be excellent spot from which to view the whole island and the waters around it. Trapped as he was, Dallam’s liking for the little mountain swelled until he had made vow to himself: he would climb that mountain as soon as he set foot ashore, before he’d even paused for food or for drink, in fact.

Dallam’s fellows aboard the boat seem to have been less keen, but he worked on them; he had days to do so after all, and eventually he’d extracted commitments from two of them: Michael Watson, Dallam’s joiner, and Edward Hale, a coachman (The Hector was also carrying a coach as a gift for the Sultan’s mother, an immensely powerful figure in her own right), would be joining him on his little hike up the hill, and Dallam would not let them forget their promises.

The day came, and a small payment to some of the ship’s sailors secured their passage in a little boat to near the foot of the hill. It was early in the morning, and the trio began their climb. Having received stern instructions while aboard that they were not to carry weapons, they had only “cudgels in [their] hands,” and perhaps that helps account for Watson’s apprehensions.

Dallam describes their first encounter on the hill:

“So, ascending the hill about half a mile, and looking up, we saw upon a story of the hill above us a man going with a great staff on his shoulder, having a clubbed end, and on his head a cape which seemed to us to have five horns standing outright, and a great herd of goats and sheep followed him.”

The “great herd” gives a pretty clear indication of the man’s real business there on the green slopes, but it was still all too much for Watson: the clubbed staff, the horned cape, their lack of weapons. Watson fearfully complained that surely these were savage men on this island, men who would certainly do them wrong. He was convinced to go a little higher, high enough to convincingly identify the herdsman as, in fact, a herdsman, but that was it. Michael Watson, if our narrator is to be believed, spent the remainder of the morning hiding in a bush, and Dallam and the coachman carried on, Hale saying “something faintly that he would not leave [Dallam], but see the end.”

A little way up the hill, and the now-duo came upon another local inhabitant, and he also did not strike them down, only bowing towards them with a hand on his breast and smile to his face. This, Dallam seems to have taken as solid proof “of what people they be that inhabit here,” but Edward, who Dallam at this point in the story began to call Ned, was less confident. He was all for going back at once. Dallam, however, asserted that his oath to himself would allow nothing less than as far as they might possibly go. So, go they did, all the way up.

The top of the hill was not only a very pleasant place from which to view the island and the sea. It was also occupied by at least two buildings. The first one, Dallam tells us, was small, square, and made of limestone. It had housed an anchorite (a religious devotee bound by oath to an enclosed space) until only recently, and Dallam writes that she had “died but a little before [their] coming thither, and that she had lived five hundred years.” At the other, across the green, a man inside passed a copper kettle to another outside.

Ned saw no reason to go closer, but Dallam, as you might have gathered, was not the sort of tourist who retreated to the comforts of his hotel room and locked the unfamiliar world outside. He seems to have been driven by the confidence of a craftsman whose organ had, he will sometimes mention, been approved of by Queen Elizabeth herself, and also by a tremendous curiosity. During this voyage, he’d try to speak with Syrian soldiers, wonder at his first sight of carrier pigeons at work, and find occasion to peer in at the Ottoman Sultan’s concubines as they played with a ball. Here, after a morning’s uphill walk in hot weather, he was also driven by thirst.

Waving aside Ned’s protests, he went forward (“boldly,” he says), and by gestures made it known to the man with the kettle that he wanted to drink. The stranger did not offer him water though. Instead, he pulled up a carpet that lay against the wall and produced 6 bottles of wine and also a silver bowl which he soon filled with red wine and handed to Dallam. Ned was still questioning the wisdom of all of this from a little ways off, but Dallam drank from the bowl and found it to be “the best that ever [he] drank.” The bowl was refilled, this time with white, and this wine, Dallam pronounced, was even better than the first.

Now, Dallam wondered how he might repay the man for his hospitality. The cautious Ned consented to come forward and take a little water, and Dallam brought out the only money he had on him, a silver Spanish coin; it was not accepted. Then, he produced a decorative knife he had in his pocket. It was gilded, graven, and sheathed, and the man was very pleased with this. Dallam and Ned were promptly ushered round the corner and into what they realized was a chapel, complete with a priest giving mass, candles burning, and strange and unfamiliar decorations all about. The service made no sense to either Englishman, but soon it was over and they were brought into another space:

“… he led us through the chapel into the cloister, where we found standing eight very fair women, and richly apparelled, some in red satin, some white … their heads very finely attired, chains of pearls and jewels in their ears, seven of them very young women, the eighth was ancient, and all in black. I thought they had been nuns, but presently after I knew they were not.”

There in the cloister, the two were settled down to a meal of “good bread and very good wine and eggs.” Ned still would only drink water, but Dallam indulged himself fully, and wondered at the women, three of whom were standing very close now, looking on. He “knew they were not nuns,” but he wasn’t sure exactly how to proceed. He offered one a bowl of wine, but she would not accept it. He tried again with his Spanish silver, but this too was rejected. He produced another of the decorated knives and pressed that on the older woman who at first would not take it, but then did. The group of women gathered around it, seeming to admire it, he thought, and then bowed towards him in thanks. He was no closer to a successful transaction.

Shortly after, he and Hale left in good spirits, doubtless energized by the turn the day had taken. They collected an indignant Watson from his bush, likely quite sore and badly in need of refreshment, and they went down into the town, finding others from their ship in a house marked with a white horse. Their friends within were at first angry, saying they’d looked everywhere and thought the worst, but then, Dallam writes, “When [he] had told them all the story, they wondered at [his] boldness, and some Greeks that were there said that they never heard that any English man was ever there before.”

So interested was Dallam’s audience, that nine of those present decided to go immediately up for a look themselves. Their storyteller being too tired to make the walk again that day, they hired a local as a guide, and so they came to the house on the hill with information he had lacked. The thing to do, he later learned, was to go first into the chapel and to make an offering of money there, “as little as they would,” and then “they should have all kinds of entertainment.” Despite their guide, the party missed the easiest path up, and some fell and “broke their shins.” However, the whole thing seems to have been a tremendous success, enjoyed by all despite the shin breaking (which was perhaps not as bad as it sounds). Dallam wrote that, “very late in the evening, they returned safely again, and gave [him] thanks for that which they had seen.”

It’s an odd little story, one in which the narrator is ultimately unsuccessful, but also entirely unbothered by his failure. He seems to absolutely delight in showing his comrades to be buffoons (“… and laughed at him – as indeed they might, for he behaved himself very foolishly.”), or cowards (“Michael Watson, for shame, would not go in with us.”), or both. He seems to equally enjoy portraying himself as boldly venturesome, the first Englishman up the hill, a trail-blazing tourist who left his trembling companions behind to clasp hands with the locals and drink their wine. However, we also see him at a loss, unsure of what was to be done, first in payment for the wine, and then in the question of the women, stumbling where his shipmates would later succeed.

He doesn’t seem to overly regret his missed sexual opportunity, though. He’d enjoyed his little adventure on the Greek hilltop that day, with its thrill of the unfamiliar and the best wine he’d ever tasted. He’d enjoyed it enough to devote an unusually long passage of his writing to the day. We don’t know what Dallam intended to do with this writing; despite the apparent interest in all things Ottoman at the time, he did not publish after returning from his very close encounter with the Sultan. But he seems to have wanted to remember his morning in the unfamiliar house, and his glee at the discomfort of Michael and Ned.

Sources

Dallam, Thomas, John Covel, and James Theodore Bent. Early Voyages and Travels in the Levant. London: Hakluyt Society, 1893.

Chamberlain, John. Letters Written by John Chamberlain During the Reign of Queen Elizabeth. London: Longmans, Green & Co., 1861.

Devon Field is a history podcaster with a Humanities M.A., telling the stories of lesser known historical figures and, through their narratives, exploring their context and place in larger events. Particularly, he’s interested in the Late Medieval and Early Modern periods and their travellers, figures that passed between cultural worlds and revealed sometimes surprising connections. You can hear more about Thomas Dallam and others like (and unlike) him on the Human Circus podcast.

Website | Twitter

This is great. It would actually make for a brilliant short, comedic film, or even a tongue-in-cheek comic.

LikeLike

Thanks! I love the comic idea actually.

LikeLike

[…] I wrote something last week for Dirty, Sexy History, a site which regularly hosts really interesting history writing on everything from boxing to horrific surgeries of the past. You can read it here. […]

LikeLike